Today, amongst all living snakes, only male boas and pythons keep vestiges of limbs: two tiny spurs located near their cloaca, used for gripping the female while having sex. But snakes evolved from legged reptiles, like monitor lizards, with which they share some traits (like similar tongues and venom) about 150 Ma ago. A fossil Lebanese snake preserved in limestone and discovered near the village of al-Nammoura, in 2000, confirms this fact: it had two hind legs. So far, scientists have found only a handful of fossil snakes proving their evolution from ancient lizards.

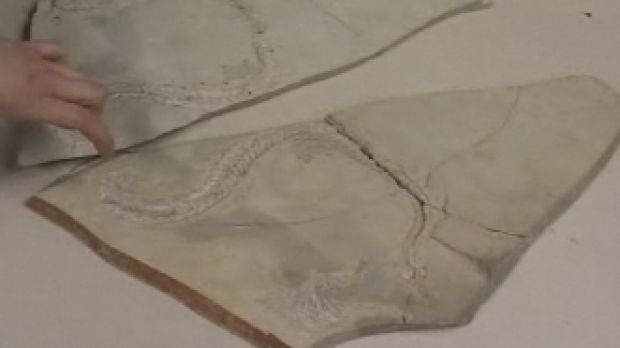

A team at the European Light Source (ESRF) in Grenoble, France, used intense X-rays to show that the snake embedded in the rock, and having one visible leg, had another one located just under the surface of the limestone slab.

"We were sure he had two legs but it was great to see it, and we hope to find other characteristics that we couldn't see on the other limb," said Alexandra Houssaye from the National Museum of Natural History, Paris.

The 85 cm (33in) long snake was baptized Eupodophis descouensi and it is 92 Ma old (from the Late Cretaceous, the last period when dinosaurs lived).

The fossil bones were divided across the two inner faces of the thin limestone block that was broken apart; part of the spine was missing and the tail vertebrae had detached and moved near the head of the snake.

The stumpy limbs were just 2cm (0.8in) long and most likely useless, but they have clearly visible femur (thigh bone), fibula and tibia (ankle bones). Scientists still cannot say what made snakes lose their limbs: a burrowing subterranean life or an aquatic sea life (mosasaurs, huge sea lizards related to the monitor lizards, dominated the seas of the Late Cretaceous). These ancient bipedal snakes could settle the debate.

"Every detail can be very important in establishing the great relationships and that's why we must know them very well. I wanted to study the inner structure of different bones and so for that you would usually use destructive methods; but given that this is the only specimen [of E. descouensi], it is totally impossible to do that. 3D reconstruction techniques were the only solution. We needed a good resolution and only this machine can do that," Houssaye told BBC News.

The team used an X-ray computed laminography, which delivers complex 3D images using hundreds of intertwined 2D images. The 3D images can be detailed to just millionths of a meter. The technique showed that the second leg embedded inside the limestone was bent at the knee.

"In most cases, we can't find digits; but that may be because they are not preserved or because, as this is a vestigial leg, they were never present," said ESRF's resident paleontologist Paul Tafforeau.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //