Some 12,000 years ago, a massive methane emission was recorded on our planet, but its source has still remained a mystery to this day. Some researchers have argued that the release of sea floor hydrate deposits, as in mostly methane, could have had something to do with it, but a recent analysis of the largest sample of Greenland ice ever investigated has shown that this hypothesis does not hold water. The find, which was published on Friday in the journal Science, brings ease to those who have feared that this methane source will make a powerful contribution to accelerating global warming in the future.

According to the recent investigation, the methane emissions that took place at the end of the last Ice Age may have actually come from expanding wetlands in the Northern Hemisphere. A period of abrupt warming had preceded these events, and experts say that the natural emission rate of marshes and swamps is compatible with the levels recorded for the period in question. In order to back up this theory, the researchers have cut thousands of pounds of ice from the edge of the Greenland ice sheets, hoping to find a sample that was exposed to the air 12 millennia ago.

“To get enough air trapped in ice to do the types of measurements we needed, it took some of the largest ice samples ever worked on. The test results were unequivocal, but it was a lot of heavy lifting. It was like working in a quarry. We could have used some help from the OSU football team,” international expert on using ice samples to explore ancient climate Edward Brook, who is also an Oregon State University professor of geosciences, said.

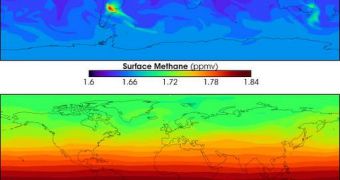

Understanding the flow of methane in nature is crucial for the development of new and accurate climate-change models, the researchers maintain. It's one of the most potent greenhouse gases in existence today, and its concentration has significantly increased since the Industrial Revolution, mostly due to human activities, such as agriculture, fossil fuel exploitation and burning, and even landfills.

For instance, the natural gas, which is used to warm homes and power a large segment of the industry, is made up almost entirely of methane. The smoke generated by burning coal also produces important quantities of the chemical, which, in large enough concentrations, has the ability to change the global weather patterns.

“There are hundreds to thousands of times more methane trapped in sea floor deposits than there is in the atmosphere, and it's important that we know whether it's stable and is going to stay there or not. That's a pretty serious issue,” Brook added.

“The data made it pretty clear that sea floor methane hydrates had little to do with the increase in methane thousands of years ago. This largely rules out these deposits either as a cause of the warming then or a feedback mechanism to it, and it indicates the deposits were stable at that point in time. The increased methane must have come from larger or more productive wetlands that occurred when the climate warmed,” he concluded.

According to statistics, a certain amount of methane in the atmosphere has the ability to cause about 21 times the amount of pollution that the same quantity of carbon dioxide does, in a 100-year interval. At this point, methane accounts for about 20 percent of the warming potential generated by GHG in the world.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //