Scientists at the University of California in Irvine (UCI) have recently demonstrated, in a study on college students, that memories once thought lost actually still reside within the brain. The find was made using advanced brain-imaging techniques, the experts report in the latest issue of the journal Neuron. The main question that arose after this find was made was what precisely caused the brain to forget these memories, or simply become unable to access them, despite them still being there.

“Even though your brain still holds this information, you might not always have access to it,” UCI neurologist Jeffrey Johnson, the author of the report, says in the Wednesday issue of the journal. He adds that recalling a certain memory triggers inside the brain the same activation patterns that were generated when the memory was first formed. Still, along the way, something happens, in that these patterns must suffer some modifications, if they become unrecognizable. What these changes are is still a mystery, Wired reports.

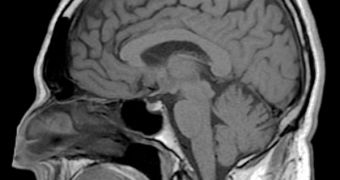

Referring to lost details, Johnson says that, “It wasn’t quite clear what happens to them. But even when people claim that there are no details attached to their memories, we could still pick some of those details out.” The new studies were conducted using functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) on 11 female students and five male students. They were shown a list of words, asked to spell them backwards, and then think of how an artist would image these words. Twenty minutes later, they were asked to remember what they could of each word.

“What I think is cool about the study is that the degree of cortical reinstatement [the triggering of the original patterns] is related to the strength of our subjective experience of memory,” Sanford University memory researcher Anthony Wagner, who has not been part of the new research, shares. It's also unclear at this point exactly how memory degradation works, and what time it takes for the signals to disappear. “We can only speculate that this is the case,” Johnson concludes, speaking about the possibility that, indeed, memory persists over weeks, months, and even years.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //