The results of a new analysis conducted by experts at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) say that the effects and spread of global warming could be reduced if emissions of greenhouse gases other than carbon dioxide are regulated as well.

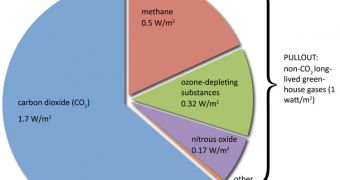

Granted, CO2 accounts for a level of warming of no less than 1.7 Watts per square meter. The second most important contributor is methane, which is responsible for warming Earth by 0.5 W/m2. Ozone-depleting substances, nitrous oxides and other chemicals make up the rest.

By targeting them rather than CO2 exclusively, the progress of climate change could be slowed down sufficiently enough to allow authorities time to debate the thorny political issues associated with reducing carbon emissions.

Details of the new investigation were published in the August 3 online issue of the top scientific journal Nature. The study was conduced by NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory (ESRL) scientists Stephen Montzka, Ed Dlugokencky and James Butler.

While talking to other scientists at the 2009 United Nations’ climate conference in Copenhagen, the three got the idea to investigate if reducing non-CO2 greenhouse gases (GHG) emission would have any discernible influence on global warming.

“We know that recent climate change is primarily driven by carbon dioxide emitted during fossil-fuel combustion, and we know that this problem is going to be with us a long-time because carbon dioxide is so persistent in the atmosphere,” Montzka explains.

“But lowering emissions of greenhouse gases other than carbon dioxide could lead to some rapid changes for the better,” the expert adds. Most other GHG gases tend to have a much shorter atmospheric life than carbon.

As such, their direct radiative forcing – which is a measure of the warming influence they have on the planet – could be reduced much faster than in the case of CO2. While carbon remains in the air for millennia, the other chemicals could be removed within two to three decades.

However, the new report admits that our society is unlikely to have the necessary will to enforce these cuts, especially considering that this would imply significant lifestyle changes on our part. As such, GHG concentrations are expected to continue to increase over the coming years.

Montzka adds that cutting non-CO2 GHG emissions alone is unlikely to cause any significant changes in global warming patterns over the next four decades. Effects will most likely begin to be felt later on.

The only way to render this technique of fighting climate change effective is to introduce at least mild to moderate carbon emissions cuts in the scheme as well.

“The long-term necessity of cutting carbon dioxide emissions shouldn’t diminish the effectiveness of short-term action. This paper shows there are other opportunities to influence the trajectory of climate change,” Butler explains.

“Managing emissions of non-carbon dioxide gases is clearly an opportunity to make additional contributions,” the expert concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //