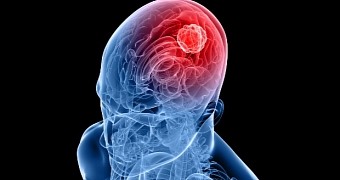

In a new study in the journal Cell Reports, a team of researchers at the University of Florida and their colleagues detail their work developing a mechanism to slow the growth of deadly brain tumors.

The experiments, so far only carried out on laboratory mice, revealed that glioblastomas, described by medical experts as highly invasive brain tumors, take longer to spread when communication between the cells that comprise them is shut down.

To disrupt effective cell-to-cell communication in the tumors growing inside the brains of the mice they experimented on, the University of Florida scientists focused on a channel that the glioblastoma cells relied on to pass molecules from one another.

When this channel was blocked, the tumor cells could no longer pass chemical messages between them, and so the growth of the glioblastomas considerably slowed. Thus, the rodents lived about 50% longer than they would have if left untreated.

“The rapid spread of a common and deadly brain tumor has been slowed down significantly in a mouse model by cutting off the way some cancer cells communicate.”

“The technique improved the survival time for patients with glioblastoma by 50% when tested in a mouse model,” the research team wrote in a report describing their work.

The treatment might also work on human patients

Presently, glioblastoma is the most common brain tumor diagnosed in adults. Since this type of brain tumor is particularly aggressive, patients have a life expectancy of merely 12 to 15 months following diagnosis.

Although they have until now only experimented on animal models, the University of Florida scientists and fellow researchers are confident that their idea to slow the growth of glioblastomas by shutting down communication between cells could also work on people.

If not cure them altogether, this treatment could at least buy glioblastoma patients some more time. If the treatment proves at least as effective as it was when tested on mice, patients could be looking at a life expectancy of 20 to 23 months rather than just 12 to 15.

In an interview, University of Florida specialist Loic P. Deleyrolle explained that, even if found safe and effective in a clinical trial involving human patients, the treatment would be recommended to patients alongside chemotherapy and radiation, just to cover all the basis.

“When it comes down to treating such a complex disease, there isn’t one magic bullet. You have to come up with complex, multiple approaches,” the researcher said.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //