Scientists have been trying their hand at creating brain-to-brain networks for a few good years now. At first, they experimented with animals. As of recently however, they've been dabbling in brain-to-brain connections between human volunteers.

One such experiment, hailed as the most complex of its kind so far, is described in a study published in the journal PLOS ONE this Wednesday, September 23.

Here's a run through

This latest attempt as proving mind meld possible, the work of a team of researchers at the University of Washington in the US, came down to linking the brains of two volunteers so that they could play a question-and-answer game together.

The volunteers were never in the same room and didn't get to actually speak to each other while the experiment was ongoing. All the same, one of them managed to guess what the other was thinking about, the research team explains.

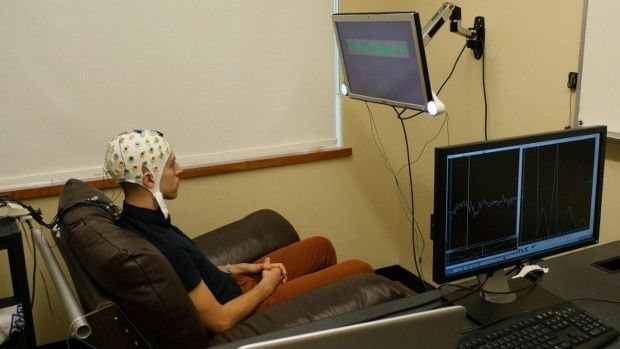

At first, the study participants were each asked to wear a cap connected to an electroencephalography (EEG) machine that served to record their brain activity. Then, one of the volunteers was shown a photo of, say, a dog or another object.

The other volunteer didn't get to see this photo. What they were presented with was a list of objects and specific questions associated with them. By clicking on a mouse, they could send a question of their choosing to the other volunteer.

This volunteer, the one who had seen the photo, would answer “yes” or “no” by focusing on lights fitted to the monitor in front of them. If they wanted to say “yes,” the other study participants would receive a strong jolt.

This jolt stimulated their visual cortex and so made them see a light flash before their eyes. After sending enough questions and receiving enough such inputs from their collaborator, the volunteers could guess the mysterious object.

No, nobody cheated

All in all, the University of Washington research team experimented on five pairs of volunteers. The scientists say they made sure the study participants could only communicate via brain signals picked up by the electroencephalography machines and then sent via the Internet.

Plainly put, they are pretty darn sure nobody cheated and that the volunteers made to guess the objects the others were thinking about only managed to do so by interpreting brain signals sent their way in response to the questions they had asked.

Apparently, the study participants assigned the role of inquirers, i.e. the ones not looking at any object and asking the questions - managed to accurately interpret the “yes” or “no” answers they got and guess what the other volunteers had on their mind in 72% of the games played.

“This is the most complex brain-to-brain experiment, I think, that’s been done to date in humans. It uses conscious experiences through signals that are experienced visually, and it requires two people to collaborate,” study leader Andrea Stocco explained in a statement.

The research team is now planning to experiment with what they call brain tutoring, i.e. trying to determine whether signals can be sent between a healthy brain and an impaired one, or if maybe proper knowledge can be transferred from one person to another via brain signals.

They also plan to test if it might be possible to transfer states. For instance, the scientists want to see whether brain signals produced by an alert person and sent to a sleepy one can help the latter wake up in response and become more focused on solving a task at hand.

“Evolution has spent a colossal amount of time to find ways for us and other animals to take information out of our brains and communicate it to other animals in the forms of behavior, speech and so on. But it requires a translation. We can only communicate part of whatever our brain processes.”

“What we are doing is kind of reversing the process a step at a time by opening up this box and taking signals from the brain and with minimal translation, putting them back in another person’s brain,” said specialists Andrea Stocco.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //