When average global temperatures reached record-high values in 1998, this event was in tune with scientific predictions of how global warming would evolve. However, in 1999 and subsequently all years since, the trend has been below predictions, and a new investigation finally reveals why.

The mismatch between predictions and recorded value allowed climate change skeptics some wiggle room, and made them bolder in declaring that humans are not influencing global warming. The inability to explain why the trend was abating reduced the credibility of climate sciences somewhat.

At first, researchers believed that the data they have collected since 1998 contains a lot of noise, a statistics term for lack of resolution and accuracy. Another explanation was that natural variations were causing temperatures to drop below expected levels. The new study shows that was not the case.

In order to prevent any confusion, it is worth nothing here that average atmospheric temperatures continued to increase beyond 1998. The issue is that they did so slower than researchers predicted.

While skeptics were busy pointing out the absence of explanations for this phenomenon, climatologists were searching for the location or systems where the missing heat continued to accumulate. Experts knew that the extra heat did not disappear, but rather hid somewhere.

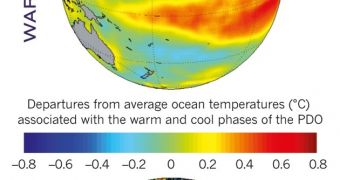

In a flood of new studies, the heat was revealed to have been hidden by the Sun, volcanic eruptions, or particulate emissions from China. However, the new investigation shows that the world's oceans are the most likely culprits, storing the heat within massive reservoirs in the Pacific Ocean and elsewhere.

The El Niño atmospheric oscillation that occurred between 1997 and 1998 is believed to have pumped massive amounts of heat out of the equatorial portions of the Pacific Ocean into the atmosphere. The ocean heat deficit this extreme event produced lasts to this day, cooling the world's climate.

“The 1997 to ’98 El Niño event was a trigger for the changes in the Pacific, and I think that’s very probably the beginning of the hiatus. Eventually, it will switch back in the other direction,” says National Center for Atmospheric Research climate scientist Kevin Trenberth.

The problem is that when the Pacific Ocean snaps back from its cold spell, the planetary climate system is likely to take a pounding. Average atmospheric temperatures are likely to take a jump upwards, too, Nature News reports.

“If you are interested in global climate change, your main focus ought to be on timescales of 50 to 100 years,” Massachusetts Institute of Technology climatologist Susan Solomon has to say for climate skeptics who argue that two decades of imprecise data are enough to discredit anthropogenic global warming.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //