For the better part of the last 150 years, scientists have been trying to figure out exactly why inhaling anesthetic compounds causes unconsciousness. Researchers in the United States say that they may have found at least a part of the correct answer in a new study.

People take the fact that anesthesia works as a given, but the fact of the matter is that doctors don't know why it works, especially when it comes to compounds that need to be inhaled in order to work.

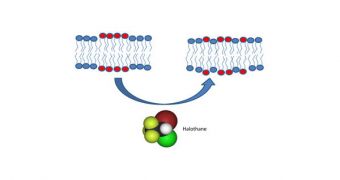

In a recent investigation, scientists at the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) believe that the chemicals change the organization of fat molecules called lipids in the outer membrane of cells.

This could be altering the membranes' ability to send out electrical signals, therefore impeding inter-cellular communications. This has been suspected since the turn of the 20th Century, but no one was able to prove that these changes actually took place.

“A better fundamental understanding of inhaled anesthetics could allow us to design better ones with fewer side effects. How these chemicals work in the body is a scientific mystery that stretches back to the Civil War,” NIST Center for Neutron Research (NCNR) scientist Hirsh Nanda explains.

One of the main points of contention in the past was that no one was able to demonstrate that anesthetics were capable of instilling a significantly-large change in the physical properties of cellular membranes.

In the meantime, biologists were able to gain a deeper understanding of how membrane conducts called ion channels work. These structures are in fact large proteins, embedded in the lipid molecules that form the outer layers of cells.

“That’s where we picked up the thread. We had been looking at how different types of lipid molecules affect ion channels,” Nanda explains. The joint team focused its attention on a single type of lipids called rafts, which are more ordered and less fluid than other lipids in cellular membranes.

“We decided to test whether inhaled anesthetics could have an effect on rafts in model cell membranes. No one had thought to ask the question before,” the expert adds.

The study – conducted using a neutron and X-ray diffraction device – revealed that exposing cellular membranes to an inhaled anesthetic led to the rafts growing disorderly, freely mixing their lipids with the surrounding membrane.

“We feel the discovery has opened up an entirely new line of inquiry into this very old puzzle,” Nanda concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //