A new research by experts at the Washington University in St. Louis (WUSL) School of Medicine (WUSM) suggests that the susceptibility babies display to developing common colds may be determined by innate difference in immunity. These variations can be detected at birth.

In other words, a simple test can detect whether infants' innate immune responses are strong enough to avert the development of common colds during their first year of life. On average, those with a strong response get sick a lot less often than their peers, the group reveals.

This study is very important, because respiratory illnesses are relatively common in babies, especially during their first year of life. In some cases, common colds can evolve into lung infections that can jeopardize the babies’ lives.

Details of the new research appear in the May issue of the medical Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. WUSM assistant professor of medicine, Kaharu Sumino, MD, was the first author of the research paper.

“Viral respiratory infections are common during childhood. Usually they are mild, but there’s a wide range of responses – from regular cold symptoms to severe lung infections and even, in rare instances, death,” the investigator explains.

“We wanted to look at whether the innate immune response – the response to viruses that you’re born with – has any effect on the risk of getting respiratory infections during the baby’s first year,” she adds.

In order to establish this correlation, investigators harvested umbilical cord blood samples from 82 infants born to mothers in the Urban Environment and Childhood Asthma (URECA) trial.

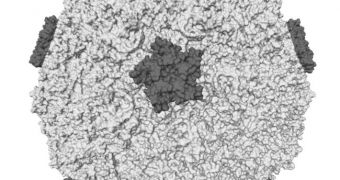

The group was especially interested in interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma), a specific immune system response that is triggered when viruses infect the body. The efficiency of the process depends on the cells responsible for releasing IFN-gamma when they encounter pathogens.

This immune response is extremely important for the body, since its primary function is to stop viruses from replicating. Other sections of our natural defenses are then charged with killing off remaining microorganisms, and tidying up.

“Ideally, if these results are confirmed, we would like to be able to intervene based on knowledge of the innate IFN-gamma response. We’re not there yet – measuring IFN-gamma levels is complex,” Sumino explains.

“But in the future, if we can develop a relatively easy way to find out if someone has a deficiency in this system, we would like to be able to give a drug that can boost the innate immune response,” she concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //