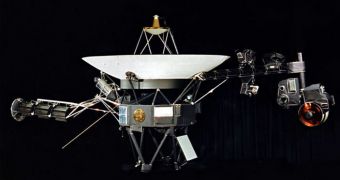

In a life briefing held on Thursday, April 28, officials at the American space agency said that the two Voyager space probes NASA launched more than three decades ago are now nearly at the edge of the solar system. The instruments are still operational, even after all this time.

These two spacecraft are the farthest man-made objects in the solar system, and they are the first ones to reach the boundary of the solar system. This is the area where the heliosphere – the protective bubble generated by the Sun- ends, and the interstellar space permeating the Milky Way begins.

For more than 30 years, the Voyager probes have continuously sent back data that led to impressive discoveries, and apparently they are continuing this tradition even today. The two were launched in the late 1970s, and are expected to continue their operations for many years to come.

“It's uncanny. Voyager 1 and 2 have a knack for making discoveries,” explains investigator Ed Stone, who is based at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), in Pasadena. He has been a scientist with the Voyager Project since 1972, Daily Galaxy reports.

While Voyager 1 got the chance to visit only Jupiter and Saturn on its way towards the edges of the solar system, Voyager 2 took advantage of a rare planetary alignment to fly past Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. Even today, it is the only spacecraft to ever fly past Neptune and Uranus.

Some of the most important discoveries made by the probes include the icy geysers that shoot out of the Neptunian moon Triton, the methane rains that drench the Saturnine moon Titan, evidence for a liquid ocean under the surface of the Jovian moon Europa and so on.

The Voyager spacecraft are now located at the end of the heliosheath, which is an area of turbulence surrounding our solar system like a ring. At this location, it's still difficult to say whether the two are still in the solar system or not. This is extremely interesting to researchers.

If they manage to move past this boundary, the probes will become the first spacecraft ever to reach the Milky Way's interstellar medium. Analysis conducted there would provide us with more clues on how the galaxy evolved, and will also help experts define some of its traits better.

“In many ways, the heliosheath is not like our models predicted,” Stone explains. However, there is plenty of time for the Voyager probes to come up with the answer. They will remain operational until at least 2020, thanks to their nuclear-powered engines.

“The heliosheath is 3 to 4 billion miles in thickness. That means we'll be out within five years or so,” the Caltech expert adds. At this point, Voyager 1 can no longer detect solar winds at its location, but astronomers believe that this is because the radiation simply changed direction.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //