Microorganisms are apparently teaming up against humans, the results of a new study suggest. Experts have found evidence that a parasite's ability to harm the people it infects is considerably boosted if the organism itself is infected with viruses.

The research team that conducted the new work is based at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland and at the Washington University in St. Louis (WUSL) School of Medicine (WUSM).

Details of their research appear in the latest issue of the top journal Science. The work could have considerable implications for research, as it could guide experts on unexplored roads towards developing new drugs and therapies against microorganism infections.

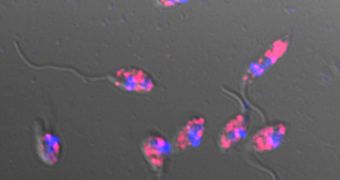

The new investigation was primarily conducted on the parasite called Leishmania, which infects humans too. The microorganism generally triggers an immune system response when it invades.

Among the first cells to respond are macrophages, cells that play a critically-important role in protecting our bodies from harm. But experts found that Leishmania can be infected by viruses.

When this is the case, the attack macrophages mount can end bad. In animal models, the infection becomes more aggressive than usual. In humans, it could be that such an interplay of factors may be responsible for destructive forms of the conditions, which prevail in Central and South America.

“This is the first reported case of a viral infection in a pathogen of this type leading to increased rather than reduced pathogenicity,” WUSM expert Stephen Beverley, PhD, explains.

“It raises a number of important questions, including whether we can use antiviral strategies to reduce the damage caused by forms of Leishmania that carry viruses,” the investigator goes on to say.

He holds an appointment as the Marvin M. Brennecke professor at the WUSM, and the head of the Department of Molecular Microbiology at the university. The expert says that the disease the pathogen causes – leishmaniasis – affects more than 12 million people around the world.

Some of the symptoms associated with the condition include large skin lesions, fever, and swelling of the spleen and liver. In the more serious forms of the disease, disfigurement and death often occur.

“How the virally increased pathogenicity arises is now a fascinating question in its own right. It could teach us a great deal about how Leishmania causes a severe form of the disease and potentially offer new opportunities for its cure,” Beverley concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //