If you think the kind of life we find in deep oceans, unexplored caves or boiling hot, acid rich environments is weird, you can look much closer to find even weirder home. In fact, the weirdest stuff happens so close, you can't even "look" properly at it, on your eyes.

Researchers at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) in France found an entire ecosystem of parasites on the eyes of a 17-year-old French woman.

The woman was wearing contact lenses and diluting the cleaning solution with tap water. She also wore the one-month lenses for three months at a time.

When she came to the doctor with pain and redness in her left eye, it was clear what happened, the contacts had become infected. The infection wasn't dangerous.

However, when researchers cultivated the liquid on the contact lenses they discovered several new organisms. They found three bacteria and one amoeba, all previously known.

Inside the amoeba, they found two new types of bacteria and one new type of giant virus. That's three new organisms inside one amoeba. It gets better.

The new giant virus researchers dubbed Lentille. Giant viruses, as their name implies, can be as large as bacteria and are veritable DNA replicating factories.

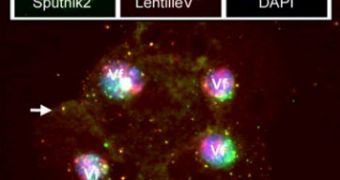

What the researchers found inside the giant virus was even more interesting, a new type of virus that infects other viruses, which they called Sputnik 2.

Sputnik 2 belongs to a family of viruses, called virophage, that can only reproduce in cells infected by other viruses. Sputnik 2 was found both inside the amoeba and inside the Lentille virus.

Sputnik 2 is only the fourth virophage ever discovered. The first ever discovered was Sputnik, Russian for "fellow traveler," by the same researchers.

The virophage hijacks the mechanisms used by other viruses to replicate itself, it is a virus' virus.

Sputnik 2 is unique among its peers in that it can insert its DNA into the DNA of the virus it's infecting, just like some viruses, HIV, herpes, can insert their DNA into the cells they're infecting.

But the rabbit hole goes even deeper. The researchers started looking at Lentille's DNA for bits that didn't belong to it or Sputnik and they found just that, strands of DNA that didn't belong there. These strands were in far greater number than the virus' own genome, 3 to 14 times more.

These strands, which have never before been seen, can attach and detach themselves to Lentille's DNA. They also "live" outside of the DNA inside the giant virus and even inside the virophage, Sputnik 2.

These DNA strands were dubbed transpovirons, after transposons – mobile DNA strands that can jump in and out of the DNA of living cells.

Transpovirons work in the same way, but they can attach themselves to viruses as well. They're really good at replicating, when a giant virus such as Lentille finds a suitable host, these strands begin to multiply "like mad."

While they don't replicate inside virophages, they may use them to go from one giant virus to another. Transpovirons are really small strands of DNA, they have between eight to six genes.

Even more interesting, the genes seem to have been borrowed from all over the place, some from giant viruses, some from virophages, some maybe even from bacteria.

Virophages work in similar ways, pieces from giant viruses, bacteria and even eukaryotic cells have been found inside Sputnik, the original.

One theory on how they acquired DNA from eukaryotic cells is that early cells may have adopted virophages and hosted them to protect them against viral infections.

Needless to say, this opens up a whole new world of exploration. There is every indication that virophages are quite common and found in many types of viruses. The discovery of transpovirons indicates that there may be countless other forms of mobile DNA strands out there. And all of this even on or in our body.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //