4 photos

Scientists have discovered that they could unleash an unusually selfish behavior by magnetically stimulating a certain portion of the brain. The subjects were still aware that their behavior was not proper but nonetheless they couldn't decide to act otherwise. This is the latest twist in the story of the research surrounding the ultimatum game.

Researchers use the ultimatum game for measuring the selfish behavior. In the game there are two players who don't know each other. One of the players is given a certain amount of money and is told to share it with the other player in whatever way s/he likes. The second player has the option of either accepting the offer or rejecting it. If s/he rejects the offer neither of the players gets to keep any money.

This game poses a certain dilemma for what it means to make a rational decision. In principle, if we take into consideration a single instance of the game, the second player should accept any offer, no matter how small because anything is better than nothing. And if the first player thinks about this s/he will naturally decide to offer a very small amount of money.

But this of course does not happen in practice. In real life the equivalents of such games are usually reiterated and one who has once been a proposer can be a respondent at a later time. So, people seem to have developed a certain sense of fairness and if they aren't offered a sufficiently large share of the pie, although less than half, they will reject it. Are they acting just out of spite? Or is spite a useful social organizer? It sure seems so because the one making the offer is usually making a relatively large offer.

"A common interpretation is that responders' behavior expresses that they would rather forgo some money than be treated unfair. Proposers' behavior is understood as combining two motives; some taste for fairness and the anticipation that small offers may be turned down," wrote Hessel Oosterbeek, Randolph Sloof, and Gijs van de Kuilen from the Department of Economics at the University of Amsterdam.

How do people behave in the ultimatum game?

From a behavioral point of view there are two main questions one might ask: Whether the size of the pie matters and whether cultural differences influence the size of the offer and the rates of rejection.

Studies have revealed that the size of the pie doesn't seem to matter very much. Even if people are offered a very large amount of money in absolute terms, which however is very small relative to what the other one would get to keep, they still tend to reject the offer. (Researchers afforded to do such studies because they conducted them in poorer countries where one dollar was much more valuable.) However, the size of the pie does matter to a certain degree and people will accept lower and lower percentages as the pie gets bigger but they are relatively resistant to this trend and don't accept unfairness easily.

Studies of cultural influences reveal some differences between countries, but not in the way you might expect. "We find no significant differences in proposers' behavior across regions," Oosterbeek, Sloof, and van de Kuilen wrote. "Respondents' behavior does, however, differ."

I have made the graphs below based on the table in their paper (which is a meta-analysis of many other individual studies conducted in various regions of the globe). Even visually the difference between proposers and respondents is stark.

The first graph roughly describes how altruistic the proposers tend to be. With the exception of the unusually selfish Spain and Peru and unusually altruistic Paraguay, Indonesia and Honduras, the proposers in most regions offered about 40 percent of the pie. It's interesting that in Paraguay the proposers often offered more than half.

The second graph reveals much bigger differences between regions. This graph describes how content the respondents were with the amount of altruism manifested by the proposers. One can wonder why France and Spain resemble in this respect Papua New-Guinea so much more than they resemble Germany or Netherlands! One can also wonder what is at the source of the relatively large difference between western and eastern United States. While the reaction in Spain could be understood as a result of the proposers' unusual selfishness, this cannot be the case in France or New-Guineea and certainly even less in Honduras.

In a certain sense this second graph reflects how critical one tends to be toward its fellows. The first graph reveals that this has little to do with what the others' are actually doing - across all regions they are all doing more or less the same thing, but the reaction differs considerably. Thus, the cultural differences seem to depend on what one is expected to do - they depend on a kind of peer pressure one is likely to feel in that region.

Observing such differences between regions researchers have naturally wondered what the underlining causes are. Various potential factors have been investigated so far:

* the country's score on Hofstede's individualism index (to what amount "everyone is expected to look after himself or herself and his or her immediate family");

* the country's score on Hofstede's power distance index ("the extent to which the less powerful members of institutions and organizations within a country expect and accept that power is distributed unequally");

* the country's score on Inglehart's traditional/secular-rational dimension (higher values signify more respect for authority);

* the percentage in country's population saying that most people can be trusted (World Values Survey);

* the country's score on 1-10 scale on the statement that competition is good (World Values Survey);

* GDP per capita (World Bank);

* Gini index for income of households per capita (UNDP World income inequality data base).

One can come up with various arguments for why such factors are relevant to the ultimatum game test of selfishness, for example one might assume that the proposer is a kind of authority so in countries with more respect for authority rejection rates should be smaller, but in the end one has to check the actual correlations between these factors and the ultimatum game results. This is what Oosterbeek, Sloof, and van de Kuilen have done. Their result is that none of these factors matter!

"...Neither the individualism index nor the power distance index has a significant effect on offered shares or on rejection rates.

...no support for the related hypothesis that responders have lower rejection rates in countries with more respect for authority; the estimate has the correct negative sign but lacks significance. Apparently, in countries in which authority is respected more, proposers anticipate this and offer less [a higher score on Inglehart's scale of respect for authority is associated with lower offers], but conditional on the offered shares responders in these countries are not less likely to reject.

...While one might have expected higher trust levels and lower competition scores to be associated with higher offered shares and with lower rejection rates, this is not supported by the results.

...Competition scores reveal no clear pattern and the correlation with other scales is also quite low.

...Clearly, neither per capita income nor income inequality explains subjects' behavior in ultimatum games."

One can start to wonder whether these differences are really real or whether they are really cultural! Insofar, they seem to be there, but no one knows what's causing them. To get a full grip of how weird this graph is, think about Bolivia: the graph says that people there are very willing to accept other's selfishness and yet the country has voted for Evo Morales and his Movement Towards Socialism party. Explain this!

Getting inside the subjects' brains

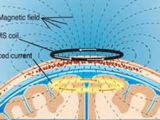

What part of the brain is involved in deciding how much to offer and whether or not to accept the offer? Brain imaging studies have shown that the action is mostly happening in the prefrontal cortex. This isn't a great surprise as this area of the brain is considered to be involved in dealing with decision making. Injuries here often cause the individual to disregard long term goals in favor the immediate gratification. This usually leads to anti-social behavior. Interestingly, in case of such injuries the individual continues to be able to evaluate what actions are good or bad but simply cannot actually follow these evaluations. This brain area is also related to personality and brain injuries of the prefrontal cortex induce changes in personality.

Neuroscientists have now invented a technique that can temporarily simulate such a brain damage. The technique, called transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), uses magnetic fields to alter the neuron firing. This can be used either to induce activity in the brain (producing hallucinations for instance) or to disturb what's already happening. The precision of targeting TMS can be as good as a few millimeters and it is now used, in conjunction to fMRI, for mapping the functions of the brain.

Neuroscientist Daria Knoch and economist Ernst Fehr of the University of Zurich were curious to find out what effect the inhibition of the prefrontal cortex would have on the way people respond in the ultimatum game. After all, this is what seems to be the big mystery.

They studied 52 young men by subjecting some of them to TMS on the right side of their prefrontal cortex, some to the left side and some, the controls, to no TMS. They discovered that 44.7 percent of the ones who were stimulated on the right side accepted unfair offers, which were accepted only by 14.7 percent of those receiving left-side stimulation and only by 9.3 of the controls. Moreover, 37 percent of right-siders accepted all unfair offers, even those that no one else would accept - such as 4 Swiss francs out of a total of 16.

The participants realized that they were being conned but simply could not refuse the offer. They also accepted the unfair offers as quickly as the fair ones, while the other subjects needed much longer to decide in the case of the unfair offers.

This is the first experiment that successfully changed somebody's decisions by influencing his brain. However, this lasts only for a short time and the brain needs to be stimulated for around 15 minutes for the effects to become visible. So the scientists aren't going to brainwash us any time soon!

The other side of the story is that it shows an interesting consequence of selfishness: it induces somebody to accept very unfair offers. The usual stories about selfishness are based on the assumption that, from a pragmatic standpoint, being selfish is always the best strategy and that there may be various reasons (involving morality) for not choosing this best strategy. But these experiments show that induced selfishness causes people to accept very lousy offers which on the long term would be disastrous. In other words, our inclination towards fairness and our ability to consider long term goals, in spite of the difficulty to predict things on the long term, appear to be connected to each other. In fact, it might be that considerations of fairness are the very method we use for coping with the unpredictability of the long term situations.

This study offers yet another possible explanation of the increasingly mysterious graph describing the cultural differences in regard to the willingness to accept other's selfishness. It might be that in regions where the future is very hard to predict people will tend to reject the offers in the ultimatum game more often. This might explain the difference between France and Spain on one hand and Germany and Netherlands on the other, or the difference between east US and west US. But it also might not explain anything.

In the end maybe the individual differences in this respect are so large that the graph itself is just a random creation of statistics rather than the reflection of a real phenomenon. Or more precisely, maybe this is a phenomenon of psychology rather than sociology. Could it be that we are all more or less similarly selfish, but very different in our tolerance for the selfishness of others?

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //