Creating artificial molecules has just become a lot easier, thanks to an innovation achieved by experts at the Scripps Research Institute (SRI), in Jupiter, Florida. A team here was able to develop a new method for producing cell membranes that are uniform in size.

The membranes are now produced on an assembly line of sorts, which guarantees that they are put together the same way every time. Using them, researchers will become able to study the inner workings of cells in much closer details.

This will also allow specialists to construct new, custom molecules, that could then be used to fulfill very specific, highly-specialized task in the human body, or in the environment. Experts could produce tumor-killing cells, or microbes that decompose spilled oil a lot faster than existing microorganisms.

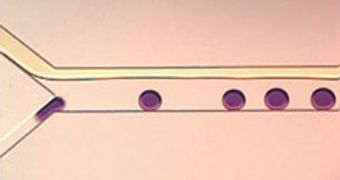

According to SRI, the new chip-based method was developed by experts Sandro Matosevic and Brian Paegel and their research team. All vesicles manufactured via this approach are uniform in size.

Given that their average diameter ranges between 20 and 70 micrometers, experts say that the membranes are large enough to accept being loaded with DNA and other biochemical machinery.

What this means is that they could basically act like synthetic cells, in which experts will for example be able to stud the proteins available in cell membranes. Numerous drugs and chemicals act directly on these proteins, but our level of knowledge about most of them is mediocre at best.

Paegel believes that the new assembly line will enable the creation of membrane proteins that will fulfill new and useful functions, of the type that did not originally evolve in the human body.

“From an evolutionary standpoint, they're just this really juicy class of molecules to target for new functions, because they do all this interesting chemistry,” the SRI expert reveals.

“The new aspect is the ability to make these giant, cellular-sized liposomal vesicles that are completely uniform in their size and their content. No one's been able to demonstrate that yet in a robust system,” adds expert Wyatt Vreeland.

“This lets us start to look at reconstituting cellular systems in vitro in a controlled way in order to investigate how different components within a cell work,” he says.

Vreeland is a research chemical engineer at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Biochemical Sciences Division, in Gaithersburg, Maryland.

The SRI group published details of its new assembly line in a paper that appeared in last month's online issue of the Journal of the American Chemical Society (JACS), Technology Review reports.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //