Over millions of years of evolution, humans have developed an advanced predictive system, that allows them to forecast events in the near future with varying degrees of certainty. A new study highlights more details on how this trait functions.

In the investigation, researchers wanted to learn to what extent does the potential harmfulness of an upcoming event affect the response that the human brain produces.

They learned that, while the cortex indeed reacts to the severity of the prospective danger, its reaction is no different when the predicted event does not take place.

In other words, if you have a scenario in which you can predict that you will see either a neutral black circle or a venomous spider, your brain will react more to the thought of the spider. This is where our survival instinct kicks in, and this is the main reasons why we have predictive abilities at all.

But the brain displays no difference in activity pattern when the expected event does not occur. In spite of the severity of predicted dangers, their absence causes the exact same neural activity patterns as if the predicted event was a neutral one.

Our ability to respond adaptively and commensurately to future threats was of great importance to our distant ancestors, who had to go through forests, savannas and other environments on foot.

Being aware of spiders, snakes and other harmful creatures was therefore paramount in these situations, and everyone caught off-guard was swiftly eaten away or killed via deadly stings, cuts and so on.

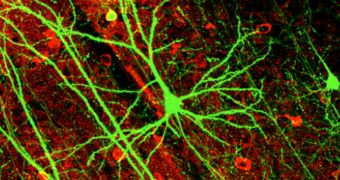

In modern studies on this predictive capability, researchers used imaging technologies to look at how the brain activates when a situation requiring prediction develops. Such was the case for the most recent study, which was carried out by Swiss experts at the University Hospitals of Geneva.

Using functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), the team was able to determine that the orbitofrontal cortex plays a critical role in making predictions, and in surveying how they turn out.

When this area of the brain is damaged, humans tend to confuse their own memories with reality, and to start anticipating events that are no longer likely to happen, AlphaGalileo reports.

The event monitoring system of the human brain was therefore found to function in precisely the same way regardless of the gravity of future events. What differs is the reaction that the person will have to the prediction, the investigators say.

The orbitofrontal cortex is “at the center of a specific cerebral network which functions as a generic outcome monitoring system,” explains first study author Louis Nahum.

“This capacity is probably as old in evolution as the instinctive reaction to threatening stimuli; its failure deprives the brain of the ability to remain in phase with reality,” Armin Schnider concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //