The study of materials at super cool temperatures and superconductivity might have reached its climax. Physics researchers at the Rutgers University studying a metal alloy, formed of a combination of cerium, iridium and indium at temperatures close to absolute zero, found evidence that electrons 'gain weight'.

By performing computer simulations that show that electrons could become over a thousand times heavier in certain metal alloys at temperatures close to absolute zero, researchers devised a model that may provide new clues on how superconductivity works, and construct new superconducting materials.

Superconductivity was discovered in 1911 by Heike Kamelingh Onnes, while studying the resistance of solid mercury at a temperature of 4.2 K, and observed that electrical resistance abruptly disappeared. The consequences of such a discovery have enormous potential, in various physical applications, such as electrical current transportation without or extremely low power loss, and the production of powerful magnetic fields.

A good example of the uses of superconductivity is the Meissner effect. A superconductor placed in a weak magnetic field will be penetrated by the magnetic lines and due to the extremely low conductivity of the supercondutor, a electric current will be induced into it, which in turn will produce an opposing magnetic field that will interact with the original. This produces the supercondutor's levitation in the magnetic field, the effect is similar to the diamagnetims.

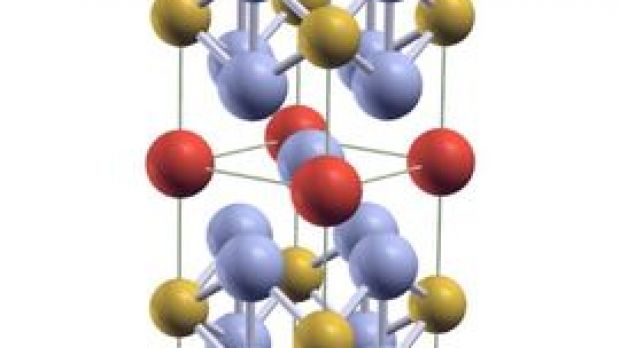

Previous experiments to understand the electrons behavior were conducted by scientists on high temperature superconducting materials called cuprates, but failed to observe the electron interaction due to the disorder in the crystalline structure caused by doping. Scientists are now using a metal alloy of cerium, iridium and indium as it has a more ordered molecular structure, enabling them to observe 'heavy' electron behavior at temperatures close to zero kelvin, at which all movement stops.

They describe the electron interactions with other particles in the alloy, to merge into a ionic fluid called "heavy quasiparticles" or a "heavy fermion fluid". Fermions are a class of particles which compose all known matter. The new compounds are relatively easy to make, structurally straightforward and adjustable, giving the scientists a new view on the properties of matter.

As an explanation of the effect, scientists say that at room temperature, electrons are strongly bound to the atoms, but as temperature drops, electrons detach from the atoms exhibiting coherent behavior.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //