Most glaciers in the Antarctic don't lie on solid rock, as many believe. Instead, they virtually float on top of underground glacial lakes, which are more like fluid ice streams. They act as a lubricant layer between the rock bed and the glaciers on top, thus allowing gigatonnes of ice to move towards the ocean. When they overflow, more water under the ice causes it to move faster, and the flow of glaciers is accelerated. Scientists now managed to observe in real time how this happens.

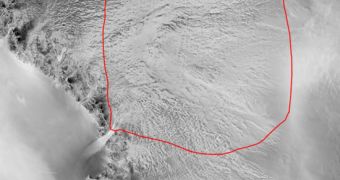

Modern ice-penetrating radar techniques allowed explorers to first get a glimpse of what's underneath the ice somewhere in late 2005. At the time, investigators noticed two underground lakes beneath Byrd glacier, in Eastern Antarctica. Surface satellite imagery, taken between 2005 and mid-2007, showed that the ice was moving more rapidly. This was also confirmed by through-ice readings, which revealed that the lakes beneath the surface were overflowing.

On the other hand, after floods, when the lakes are slowly refilling, the motion of the ice atop decelerates, and less ice reaches the ocean.

"The extra water overwhelms the sub glacial drainage system. It can't escape fast enough, so spreads out beneath the glacier bed and reduces the friction between the ice and the rock, allowing the glacier to slide faster," explains Leigh Stearns, the leader of a scientific team, based at the University of Maine.

The scientists add that there is no reason to believe that global warming has something to do with these occurrences, miles beneath the thick ice shelves of the Antarctic. Rather, scientists believe this a natural phenomenon, designed to regulate the flow of ice towards the ocean, and to maintain the integrity of the off-shore spread of ice. "It is hard to see how anthropogenic global warming would affect the base of the ice sheet," argued Andy Smith, a scientist with the British Antarctic Survey.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //