In a groundbreaking new study, a team of Australian investigators was able to develop a new method of addressing spinal cord injuries in animals. Their progress, if translatable to humans, could lead to the development of treatments that would cure thousands of people suffering from paralysis.

The condition has multiple causes, including genetic illnesses, accidents and autoimmune disorders, and currently has no cure. Experts have tried in vain to identify methods of growing nerve cells back, but the new investigation takes on a different approach.

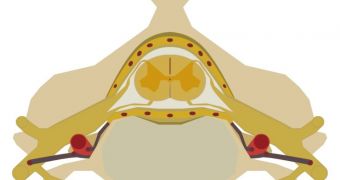

In order to understand how this works, it's important to know that the early stages of spinal cord damage look extremely similar to a bruise. But the main difference between a regular bruise and such damage is that the latter progressively degenerates.

This means that the inflammation response which is triggered after the initial damage further harms the spinal cord, leading to even more damage, and therefore more inflammation. While other approaches were meant to be used after the entire damage was done, the new one is to be used while this occurs.

Experts at the Queensland University of Technology (QUT) say that applying a special protein to the spinal cord while the damage is occurring can block the body's natural inflammatory response, reducing the amount of damage the spinal cord suffers.

“Our research is looking at the effects of adding proteins, also known as growth factors, to the spinal cord to reduce or switch off the inflammation and prevent secondary neurological damage,” explains QUT Institute for Health and Biomedical Innovation (IHBI) expert Dr. Ben Goss.

Vascular endothelial and platelet-derived proteins represent the main elements of the new treatment, and this combination has thus far yielded very promising results in animal studies. Experts conducted follow-up studies on test animals one and three months after the therapy was originally applied.

“This study has demonstrated for the first time a treatment can reduce or eliminate secondary degeneration after traumatic injury to the spinal cord,” Dr Goss explains, referring to the fact that animals treated with the protein cocktail displayed less inflammation damage in the spinal cord.

“At present spinal cord injury is permanent and irreversible, but I believe our research has the potential to improve outcomes and this might be the first step to achieving a cure,” the expert goes on to say.

The QUT team also draws attention to the fact that – if the new treatment is introduced into standard practice – speed will be the key factor to its success. This means that the proteins will have to be injected inside the spinal cord as soon as possible, in order to minimize potential damage.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //