Most of the populations of Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Polynesia, Micronesia, Melanesia and other parts of the southeastern Asia speak Malayan. These people originated in a migration of Mongoloid tribes coming from Taiwan. They first entered Philippines and, from there, colonized the whole Pacific and Indonesia. But before the Austronesian migration, the whole southeastern Asia was inhabited by Black people belonging to the so-called Black Asian race, now surviving in New Guinea and Melanesia. Pygmies seem to belong to this race, and even today, tribes of pygmies, called negritos, survive in the remote mountains of Philippines.

The first Austronesian wave, at least 5,000 years old, was made by Proto-Malayans, farming people of average height, darker skin and black hair. This people make the indigenous population of Indonesia and Philippines.

A second Austronesian wave, about 2,000 years old, came from Indochina. These are called Deutero-Malayans, have a high degree of civilization and occupy usually the coasts of the islands, being good fishermen and sailors, representing the proper Malay.

Proto-Malayans are famous for their habits of head hunting and, sometimes, ritual cannibalism. Dayaks are a famous example from the island of Borneo. Toraja, the highlanders of the southern Celebes (Sulawesi) island of Indonesia, famous for their extremely complicated and expensive burial rituals, are part of this group. 4,500 years ago, they entered Celebes onboard bizarre ships, whose memory was preserved along the time in the form of the roofs of the Toraja houses, with their raised line and elegant central curvature.

Starting with the 10th century, Bugis, an Islamized population of Malay people, started to colonize southern Celebes. This triggered bloody wars with Toraja, translated in large casualties in both camps and many prisoners turned into slaves. Towards the 16th century, the Toraja population was forced to retreat to the mountains of the inner island, where they built fortified houses.

Bugis founded strong kingdoms, like Bone, which controlled the trade of the region. They entered in conflict with the Makassar (a Malay population speaking a different language) kingdom of Gowa. The Dutch took advantage of this conflict: they allied with Bugis to defeat the kingdom of Gowa and later they extended their dominion over the Bugis.

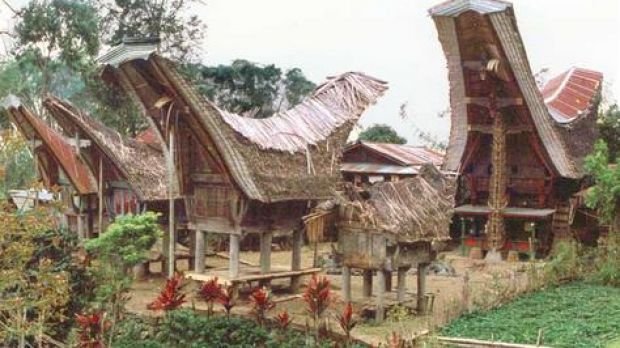

A traditional Toraja village is called tondok. The houses are aligned on the side of a main street, on an axis east-west. In front of the houses similar but smaller constructions are located. These are barns storing the rice, the so-called lambang padi. They are more numerous than the houses and built with the same care, being richly and diversely decorated.

The barns are located about 2 m (6.6 ft) above the ground, being sustained on 6 thick bamboo pylons. The houses have a larger number of pylons, and the front part of the lower space is closed with a wooden wall, forming a kind of terrace, having in front the large pole that sustains the roof, located at a height of 15 m (50 ft). The front of the houses is placed northward; that of the barns is located southward.

For the Toraja, "banua" means simply house and "tongkonan" (from "tongkan," to inhabit) refers to the traditional houses. The original houses, named so because they represent the place where parents or grandparents of a person were born, have an extremely important role in the Toraja communities. They are not individual dwellings, but they belong to a familial group of noble origin.

The Toraja society is strictly divided into castes, like in the Hindu society. The nobles (Toka Pua) make less than 10 % of the population, but own large land surfaces and dominate the social life. Only the nobles make the pompous funerary rites that last 7 days and 7 nights, with the sacrifice of at least 24 buffaloes and hundreds of pigs, with cock and bull fights and immense dancing processions. It's a way of affirming the superiority of the caste.

A woman of the noble caste could not marry a man of a lower caste, and the violation of this rule was once punished with death. Today, this rule is no longer respected, and this way a new caste appeared, that of the "small nobles" (Anak Disese).

The To makaka caste comprises free people, warriors, the small land owners (25 % of the population of Tana Toraja, which numbers 350,000 people) and To buda or To kaunan, the descendants of the former slaves. They came from the prisoners captured during the endless tribal wars, but they were treated gently, never being exploited or killed during the ceremonies asking for human sacrifices. For this purpose, slaves were bought from other villages.

The Dutch authorities, who imposed their dominion in Tana Toraja in 1905, forbade the slavery and human hunting, required for revenging the death of a relative or friend, at whose burial the gods asked for the head of the enemy as an offering.

Still, the former slaves remained with their former owners, which defended them and offered them jobs and a meaning of subsistence. They could leave the village anytime and, after their death, their body was not thrown to the pigs, but buried in a simple ceremony. In a society obsessed with preparing the moment of the death, this was an important privilege.

Only nobles could build tongkonans decorated in a specific manner. They turn into places for family meetings, when the dates of various ceremonies, marriages and inheritance sharing are fixed. The tongkonans have also a role in strengthening kinship: people are more bound to the house than to their relatives. They can enumerate easily the houses of the parents, grandparents, and even of the more remote ancestors and they consider themselves "brothers and sisters" inside a house. The tightest relationships are with the houses of their parents and grandparents, then to the origin houses. The children are members of the origin houses of both parents.

The maintenance and re-building of a tongkonan is made by all relatives, even if they no longer live in it. Often, a well state tongkonan is remade for conferring it a higher prestige in front of other houses.

The tongkonan can be decorated on the front pole (which sustains the roof) with a wooden buffalo head, with natural horns embedded in it. This is a Kabango, which can be placed only after the accomplishment of a complete funerary rite. Under it, at least 24 buffalo horns are aligned, almost down to the ground level, representing the animals sacrificed during the funerary ceremonies. The number of horns varies between tongkonans.

In case of divorce, the man must leave the tongkonan, receiving a barn (lembang padi). He can move the barn in other part. The tongkonan, once built, cannot be moved.

After the birth of a child, the father puts the placenta in a small reed basket which is buried into the eastern part of the house, a cardinal point associated with life and favorable spirits by the Toraja tradition.

Due to their proportions, the barns are more balanced and elegant than the tongkonans. Their roof does not require support pole but the building system of the barns is similar to that of the houses. The barns are made of a first layer of bamboo trunks, split and positioned just like gutter tiles, then of a thick layer of rice straw and, on the exterior, banana leaves. This succession of layers ensures not only a perfect tightness against the equatorial rainfall and a pleasant coolness in the interior. The barns do not serve just for storing rice, but it can also be a room for visitors.

Barns and houses are decorated with four colors: yellow (it symbolized the body of the gods), red (blood), white (the bones of the dead) and black (the kingdom of darkness). The leitmotif is the buffalo head, skillfully stylized, with a remarkable elegance and purity of the lines. In the front triangle, on the both sides of a central space, a cock is represented over a rosette. The bird is the mediatory between the terrestrial world and that of the paradise, the place where spirits live. His song announces the sunrise and can revive the defeated heroes. The cock appears in many Toraja myths and cosmology, as a constellation.

Other panels of the face of the house are adorned with spirals, plant forms and circles (curb lines and motifs are general in Indonesia). The whole front of the house is a symbol for the members of the family. The presentation of the katik, a mythic bird of the jungle, informs the others that the owner of the house participated in the ma'bua ritual, meant to increase the fertility of the crops.

The persons must ascend seven steps to the floor of the house, and from the trap door they enter into a room with shutters, of over 15 square meters. It is the main room of the house. At its ends, there are two additional smaller rooms. The central room is destined for the husbands but it is also the meeting place of the family during the day. The other rooms are reserved for the grandparents and children.

Furniture is scarce. People sleep directly on the floor, wrapped in sarongs, or on a thin mattress. Food is prepared at the back of the house, for avoiding fires. And, in the tight space of these houses, the dead are kept for weeks and even months!

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //