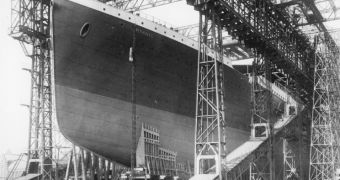

On 14 April 1912, RMS Titanic, an Olympic-class passenger liner, struck an iceberg while in the waters of the North Atlantic. Three hours later, on 15 April 1912, the so-called 'unsinkable' luxury liner sank, killing more than 1,500 people on board. Ironically, the biggest passenger liner of its time was in its maiden voyage. Titanic still remains as the worst peacetime maritime disaster in history, nearly one century after it occurred.

According to Timothy Foecke, National Institute of Standards and Technology metal expert, the true reason for Titanic's sinking is the use of low-grade rivets on some areas of the ship. Because the Harland and Wolff shipyards in Ireland were commissioned to build the ship quickly and at a reasonable price, at the same time with two other vessels, the shipyard was forced to make use of millions of low quality rivets.

"Under the pressure to get these ships up, they ramped up the riveters, found materials from additional suppliers, and some was not of quality," said Foecke.

"The company knowingly purchased weaker rivets, but I think they did it knowing they would be purchasing something substandard enough that when they hit an iceberg their ship would sink," says Jennifer Hooper McCarty, who, together with Foecke, wrote a book around this theory, called "What Really Sank the Titanic".

"I had the opportunity to study the metallurgy of several rivets. It was a process of taking thousands of images inside of these rivets, finding out what the structure was like, doing chemical testing and computer modeling. Seeing the kind of levels we saw in different areas, in different parts of the ship led us to believe they would have ordered from different people," added McCarty.

Slag, a byproduct of smelting, was found in concentrations as high as 9 percent, while high quality rivets, like those that were supposed to be used in the building of Titanic, should contain only about 2 to 3 percent slag.

"You need the slag but you need just a little to take up the load that's applied so the iron doesn't stretch. The iron becomes weak the more slag there is because the brittleness of the slag takes over and it breaks easily," explains Foecke.

With high quality rivets, the ship would have suffered a similar outcome; however, it would have taken a considerably higher amount of time to sink it. According to the investigation carried out by Foecke, the stronger rivets were expected to be used in the stern and bow areas of the ship, where stress would be greatest, albeit this was clearly not the case, since the iceberg struck the bow region.

"Typically you want a four bar for rivets. Some of the orders were for three bar," said Foecke while revealing the strength measurements for the rivets.

Criticism

"We always say there was nothing wrong with the Titanic when it left here," says Harland and Wolff yards spokesman Joris Minne.

As the Titanic hit the iceberg, it actually scraped alongside the ship, damaging the weakest rivets and putting more pressure on the strongest. "Six compartments flooded. If the rivets were on average better quality, five compartments may have flooded and the ship would have stayed afloat longer and more people would have been saved. If four compartments flooded, the ship may have limped to Halifax," concludes Foecke.

On the other hand, ex-Harland and Wolff naval engineer David Livingstone agrees to some extent with the findings of the NIST investigating team. "You can't just look at the material and say it was substandard. Of course material from 100 years ago would be inferior to material today." Titanic's sister ship, the Olympic, was built with the same materials and experienced no trouble, while the third vessel of the Olympic-class, the Britannic, was sank by a mine during World War I.

Additionally, Livingstone says he can find no reason for the use of weaker rivets in the stern and bow, but it may have had something to do with the fact that the hydraulic rivet machines were unavailable for those parts of the ship, and wider rivets were used to compensate for material characteristics. Also, the time required to sink the Titanic was exaggerated in relation to the ships of similar construction.

"The problem is not the metallurgy of the rivets, it was the design of the riveted joints," says chairman of the forensics panel of the Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers, William Garzke. If the company had used three instead of two rivets in the impact area, Titanic might have never sunk, or at least a smaller number of people would have died.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //