According to a new scientific investigation, it would appear the the mountains adorning the surface of the Saturnine moon Titan have no other possible origin than the shrinking of the celestial body itself.

The new theory goes that, as the moon is getting cooler, it shrinks, and that its surface is following the overall trend by wrinkling up. Researchers now liken it to a raisin.

There is no other possible explanation for how Titan's mountains appeared. They spread all over the planet, but cannot possibly be the result of tectonic activity.

On Earth, mountains form through a variety of methods, including sedimentation, erosion and volcanic activity. But neither of these processes takes place on Titan.

“Titan is the only icy body we know of in the solar system that behaves like this. But it gives us insight into how our solar system came to be,” says Giuseppe Mitri.

The expert is based at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena, where he is a member of the Cassini Radar team.

He is also the lead author of a new paper detailing the findings, which appears in the latest online issue of the esteemed scientific Journal of Geophysical Research.

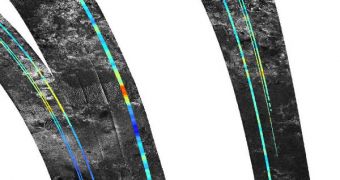

The radar data that led to the new conclusions were collected by the NASA Cassini spacecraft, an orbiter that has been observing Saturn and its moons for more than six years.

The outermost layers of the moon's crust exhibit differing densities, which may be one of the driving factors behind the way the surface wrinkles up.

Scientists now believe that Titan is cooling because it loses heat that was accumulated when it first formed, and which is supported by isotopic decay in the core.

“These results suggest that Titan's geologic history has been different from that of its Jovian cousins, thanks, perhaps, to an interior ocean of water and ammonia,” explains Jonathan Lunine.

“As Cassini continues to map Titan, we will learn more about the extent and height of mountains across its diverse surface,” says Lunine, who is a coauthor of the new paper.

He is an interdisciplinary scientist for the Cassini Mission, and is based out of the University of Rome, in Italy.

The Cassini mission is managed by experts at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), in Pasadena, California.

Follow me on Twitter @TudorVieru

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //