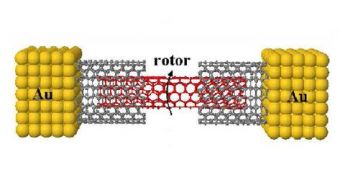

Advanced computer simulations carried out by Colin Lambert of the Lancaster University resulted recently in the design of world's smallest turbine, a device consisting of a 10 nanometer long and 1 nanometer across carbon nanotube housed inside two other wider nanotubes (see image). As electric current is pumped through the two ends sustaining the tube (rotor), the latter starts spinning. The tiny turbine may one day form the basis of world's smallest printer and could make computer memories at least 10 times smaller than those commercially available today.

Although it hasn't been built yet, Adrian Bachtold of the Catalan Institute for Nanotechnology believes that the process should be rather simple with the help of current nanotechnology. Similar devices have been previously created, yet not with carbon nanotubes but rather with DNA strands, cell transport proteins or even light sensitive molecules. The advantage of the newly designed turbine is that it's much simpler to build and operate than the rest.

Typical turbines work by making use of the energy created by a moving fluid. The carbon nanotube turbine on the other hand harnesses the energy of electrons. When current is applied electrons start circulating the rotor from one end to the other, bouncing from one carbon atom to the other. In the end, due to the configuration of the carbon nanotube the electrons will come to follow a spiral trajectory across the tube. The reaction force determined by the movement of the electrons will eventually determine a couple in the nanotube, causing it to rotate in a direction opposite to that of the electrons.

Aside from the possibility of creating frictionless rotary devices, the new turbine design could provide the means to develop atom and molecule pumps through the nanotube, for a better control in certain types of chemical reactions. "It's like a nanoscale inkjet printer", says Lambert.

Alternatively, it could be used to create arrays of tiny motors for information storing and processing.

"The work of Lambert's group is exciting, the proposed motors should be rather straightforward to fabricate", says Bachtold, who did not participate in the study. Until then however, more experiments must be carried out to confirm the theoretical predictions.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //