For cancer patients, chemotherapy is oftentimes the only possible course of treatment. Doctors discovered long ago that administering more than one drug to patients significantly improves chances of survival. Now, a study shows that the order and timing of drug administration is very important.

Scientists from the Cambridge-based Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have recently determined that giving cancer patients their drugs in a specific order and at certain intervals can significantly improve the effects of chemotherapy, without taking additional measures.

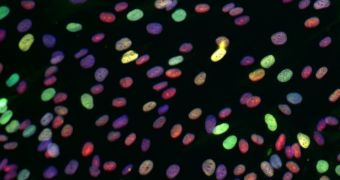

Details of the team's investigation were published in the May 11 issue of the esteemed scientific journal Cell. The research was carried out on a particularly malignant type of breast cancer cells. The group showed that staggering the doses of two chemicals improved results drastically.

The study was led by the MIT David H. Koch professor of biology and biological engineering, Michael Yaffe. Together with colleagues at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, the researchers are now planning clinical trials to test the effectiveness of their approach on cancer patients.

Erlotinib and doxorubicin, the two chemotherapy drugs that investigators analyzed, are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating cancer in humans, so the team will not have to get approval for conducting the new trials. This will enable them to obtain results a lot faster.

“For triple-negative breast cancer cells, there is no good treatment. The standard of care is combination chemotherapy, and although it has a good initial response rate, a significant number of patients develop recurrent cancer,” Yaffe says.

He also holds an appointment as a member of the MIT David H. Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research. He conducted the work with postdoctoral researcher Michael Lee, who was also the lead author of the Cell paper.

The group says that nearly 16 percent of breast cancer cases are accounted for by triple-negative tumors. Additionally, TNT are more aggressive than other forms of the condition, and have a high incidence in young women.

“We thought we would retest a series of drugs that everyone else had already tested, but we would put in wrinkles – like time delays – that, for biological reasons, we thought were important,” Lee explains.

The team was able to achieve a specific combination of drug administration orders and time delays that had unexpected results.

“Instead of looking like this classic triple-negative type of tumor, which is very aggressive and fast-growing and metastatic, they lose their tumorigenic quality and become a different type of tumor that is actually quite unaggressive, and very easy to kill,” Lee concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //