Researchers in the United States published a study in which they showed how cancer therapies that are based on stimulating the function of a specific protein have wildly varied results depending on when it is applied.

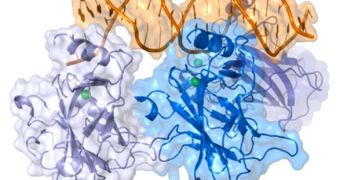

In the international scientific community, and especially among oncologists, the protein p53 is famous. Discovered in the early 1980s, it has been found to have important anti-cancer properties.

In other words, experts noticed that it can suppress tumor formation in a healthy individual, by stopping the mutated cells from reproducing and agglomerating in a specific region.

The discovery was further confirmed when experts discovered that p53 is largely inactive, or functions incorrectly, in more than half of all cancer types. They concluded that a clear link must exist, and the the molecule definitely has cancer-suppressing properties.

But, even with scientists focusing their efforts on developing methods of restoring functionality to the protein, progress in researching drugs based on it has been slow until now.

The new investigation, conducted by experts at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), basically highlights some of the possible limitation that such drugs could have, and why.

In their experiments, the MIT biologists used unsuspected mice infected with lung cancer as subjects. They used drugs that boost p53 function in the animals, and then looked at how the rodents reacted.

They found that applying the therapy in the early stages of cancer development had no effect to speak of. However, if they administered the chemical in later stages, the tumors were prevented from spreading to other organs in the body.

This means that the cancer itself was not cured, but the the onset of metastasis – the generalized spread of cancer to several or all major organs in the body – was significantly delayed.

Full details of the experiments and their outcomes were published in the November 25 issue of the esteemed scientific journal Nature.

The main conclusion is that p53-oriented drugs need to be used carefully. While they are efficient in preventing the spread of later-stage cancer, they have a tendency to spare benign tumor cells that could later turn aggressive.

“Even if you clear the malignant cells, you’re still left with benign cells harboring the p53 mutation,” explains the lead author of the Nature paper, MIT David H. Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research postdoctoral fellow David Feldser.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //