In the distant past, Mars was a wet planet, featuring lakes and an ocean on its northern hemisphere. A recent study discovered that about a third of these former lakes contain mud and clay deposits of the type of house fossilized lifeforms here on Earth.

The work is critically-important because it indicates locations where future astrobiology missions could land in order to search for signs of past life on the Red Planet. The study indicates that the number of such locations on Mars is smaller than on Earth.

This conclusion was reached after analyzing surface images collected by the NASA Mars Odyssey and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) spacecraft, as well as by the European Space Agency's Mars Express spacecraft. The work was led by experts at Brown University.

According to researchers, if life ever existed on Mars, it was most likely “headquartered” around lakes or other bodies of water. If so, then clays and mud may have trapped some of these organisms, and then solidified in time.

Landers or rovers could be deployed at these locations, and made to drill in these deposits. Specialized scientific instruments could then be used to analyze the recovered samples, and determine whether they contain any biological samples.

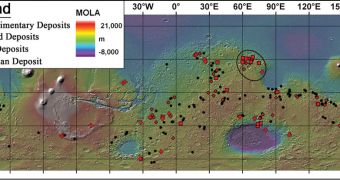

Before this can happen, scientists need to know where the most likely places to find sings of life are. In order to make this assessment, they used the three spacecraft to study light reflected by the ancient lake beds. This helped them find out which of these locations contained the materials they were looking for.

Only 79 of the 226 lake beds revealed signs of muds or clay, but that is still a fairly high number, Space reports. Planetary scientists say that this result could indicate either that Mars' geological process are not fully understood yet, or that water only endured on the neighboring world for a brief period of time.

Details of the research were published in the latest online issue of the scientific journal Icarus.

Chemists are not yet sure of how Martian water mixed with the surrounding soils, which is why they cannot accurately determine which of the two scenarios is more likely. But this question may be partially settled by the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) rover Curiosity.

When it arrives at Mars, this August, the robot will investigate clay deposits in Gale Crater, its planned landing site. “Clay minerals on Earth are a very well known preserver of the signatures of life,” says Timothy Goudge, who is the primary investigator of the MSL mission.

“On Earth, pretty much all of the lakes we see have some form of life living within the sediment, or in the lake itself. Of the possible candidates, lakes are a very good one,” he concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //