Physicists announce in a new study that they were able to prove experimentally that thermal fluctuations occurring randomly in magnetic memories can actually be put to good use. Generally, heat is regarded as the main enemy of these forms of computer memory, but the research group showed that their influence could be redirected in such a manner that the amount of energy required to store information could be significantly lowered. Details of the investigation appear in the latest issue of the respected scientific journal Physical Review Letters.

Further information on the new approach are also provided in a View point published in the latest issue of the journal Physics, a publication of the American Physical Society. The investigation was conducted by expert Markus Munzenberg, who is based at the Universitat Gottingen, and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) expert Jagadeesh Moodera. They somehow managed to turn the effects of heat back on themselves as, usually, thermal radiation is considered to be extremely dangerous for the storage of digital data.

This happens because the particle movements required in order to produce a magnetic charge, which codes for the data, tend to get scrambled as more heat is applied, eventually scrambling the information beyond any possible recognition. This is one of the main reasons why it's not recommended to keep your desktop computer right next to a heat source. The hard drive can lose all the data it contains if subjected to excessive heat for a long time. Scientists and industry engineers, who are constantly trying to build denser, smaller and faster magnetic memories, are very aware of this effect.

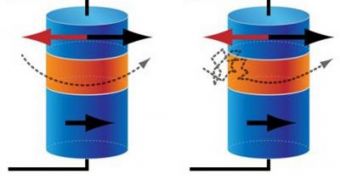

During the new experiments, it became obvious that the amount of particle acceleration that heat causes can be put to good use by relying on it to write date on magnetic memories. The researchers applied less initial current, and obtained the same result as they would have if they used more current and less heat. The experts say that thermally-assisted data writing schemes could soon become a possibility, allowing for data-storage units that would consume a lot less power than they do today, thus making computers more environmentally-friendly and energy-efficient.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //