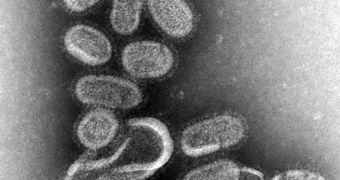

As the World Health Organization (WHO) recently announced the swine flu outbreak to be a pandemic, it has brought more attention than ever before to the dangers that the influenza virus holds. Although it's generally regarded as a mild disease, which does not cause any real damage to humans, from time to time it mutates into forms that invalidate the previous statement. Experts, for instance, say that this pandemic is the latest in a continuous row, which began in 1918, when the flu outbreak killed 40 to 50 million people in just one year, roughly the number of people who died in World War II.

To make matters worse, geneticists shared recently that the flu strain A-H1N1 (swine flu) was not a new addition to this viral family, but that it had been around for about a century, waiting for the right conditions to be met so that it broke out again. In a scientific paper published yesterday in the New England Journal of Medicine, experts argue that, for all this time, the virus has jumped from pigs to humans to birds, and that, consequentially, understanding its historic behavior may be essential to predicting how it will act from now on.

“Ever since 1918, this tenacious virus has drawn on a bag of evolutionary tricks to survive in one form or another, in both humans and pigs, and to spawn a host of novel progeny viruses with novel gene constellations,” National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases scientists explain, adding that we are currently living in a “pandemic era,” Wired informs. They also share that H1N1 was a usual part of the flu seasons from 1918 to 1957, when it got replaced by the H2N2 strain. The new virus overwhelmed the existing one, and drove it to “extinction.”

“When a new strain comes out, it overwhelms the population. Because people had no existing immunity, the new virus replicated and H1N1 got immunologically squeezed out,” University of Pittsburgh infectious disease expert Shanta Zimmer, who has been a co-author for the new paper, says. When H1N1 finally reemerged, first in 1976 (quickly contained, 230 infected, one killed), and then in 1977, in China, the Soviet Union and Hong Kong, the researchers analyzing it noticed that its genetics were not similar to those of recent outbreaks. Rather, they were more like the strain that disappeared in the 1950s.

This led researchers to assume that someone had accidentally or purposefully released it from a freezer. “From 1957 to 1977 we didn’t see any H1N1, just H2N2. Then it reemerged in 1977, kind of out of the blue. It’s circumstantial evidence, but the sudden reemergence coupled with the virus’ genetic profile makes us think it came from the accidental release of a 1950 strain,” Zimmer adds.

Columbia University Epidemiologist Ian Lipkin believes, however, that there may be other explanations as to why the strain reappeared. “There could have been strains circulating that we didn’t know about. It’s fine to speculate, but based on genetics alone, we don’t know for sure that it came from a lab,” he points out. Lipkin is also a member of the World Health Organization surveillance network, which looks after viral strains around the world.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //