In a find that could have massive implications for handling people suffering from speech disorders, experts at the Yale-affiliated Haskins Laboratories have determined that learning how to speak also changes the way sounds are heard in the human brain. The discovery, which is detailed in this week's issue of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), shows that children learning to speak, or adults learning a new language, may experience an altered perception of the sounds around them as they do so.

“We've found that learning is a two-way street; motor function affects sensory processing and vice-versa. Our results suggest that learning to talk makes it easier to understand the speech of others,” McGill University Professor of Psychology David J. Ostry says. He is also a senior scientist at the Haskins Laboratories. As the learning process develops, the expert reveals, oral fluency is considerably boosted, as is a person's ability to distinguish between sounds coming from various speeches.

“It's like being handed a two-pound weight for the first time and being asked to make a movement, it's uncomfortable at first, but after a while, the movement becomes natural. In growing children, the nervous system has to adjust to moving vocal tract structures that are changing in size and weight in order to produce the same words. Participants in our study are learning to return the movement to normal in spite of these changes. Eventually our work could have an impact on deviations to speech caused by disorders such as stroke and Parkinson's disease,” the expert adds.

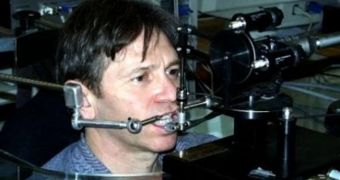

In the experiments, the scientists used a robot attached to participants' jaws to slightly alter the way their face moved while speaking. At first, the test subjects had a difficult time uttering the same words as a computer told them, but, with practice, their brains learned to overcome the existing obstacle, and to again pronounce the words correctly. The experts measured the learning process that took place based on the participants' ability to overcome the extra force that was being applied on their jaws.

“Our study showed that speech motor learning altered the perception of these speech sounds. After motor learning, the participants heard the words differently than those in the control group. One of the striking findings is that the more motor learning we observed, the more their speech perceptual function changed,” the expert adds. These conclusions could be used in the near future to devise new therapies for conditions such as Parkinson's disease, which affect the function of motor neurons in the brain.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //