A recently found fossil from Argentina's Southern Patagonia region, near Comallo, and dated 15 million years olds, seems to be the largest "terror bird", a group of giant flightless carnivorous birds called phorusrhacid, that once dominated South and North America.

First fossils of the terror birds were found in the late 1800s and are thought to have become South America's top predators after the dinosaurs died off 65 million years ago, in the absence of highly evolved mammalian predators.

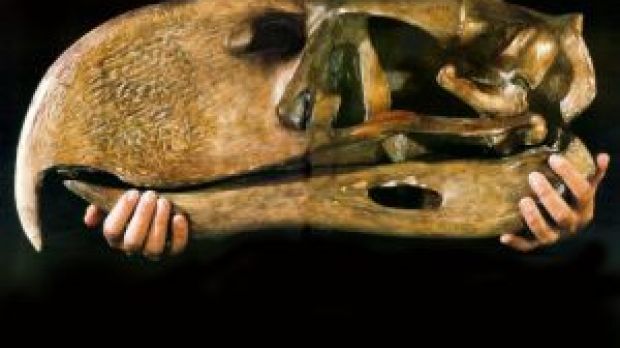

"Terror birds were the biggest birds the world has ever seen, and the new species is by far the largest terror bird yet," says paleontologist Luis Chiappe, director of the Dinosaur Institute at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, California. "Some of these birds had skulls that were two and a half feet (80 cm) in length. [They] were colossal animals," he said.

The new species, still without a name, was about ten feet (3 m) tall, 1000 pounds (400 kg) weight and had a head as big as that of a horse. Bones found are a limb bone and 28-inch, nearly intact skull. These terror birds could have swallowed dog-size prey at once.

The bird's most striking feature-literally-was its giant skull, a roughly 18-inch (46 cm) beak with a sharp, curving hook shaped like an eagle's beak. "Whether the flightless birds used their beaks to impale or bludgeon their prey is unknown, Chiappe says. But a single hit from their massive skull[s] would have killed anything immediately."

"This is by far the best skull preserved" for a large terror bird, Chiappe said.

"We also have some of the foot bones [from] the same animal, which is great, because it allows us to make inferences about the speed of this animal."

Many phorusrhacid birds were smaller species, 2 to 3 feet (60 to 90 centimeters) tall. But the largest species, like many top predators, lived in relatively small numbers, so their remains are scarce. "Over the decades [scientists] have reconstructed the gigantic members of the terrors birds as a scaled up version of the small ones," Chiappe said.

Previous reconstructions speculated the larger species as slower and clumsy, but the new skull and foot bones indicate that large terror birds were both nimble and speedy, being able to reach 30 mph.

The notion that larger species are slower is "largely incorrect," Chiappe said. "We don't really see that inverse correlation between large size and less agility."

The concept has been that - as they evolved bulkier - the birds became slower and less agile. Chiappe estimates that the new species ran as fast as modern day emus or rheas but were not as speedy as ostriches, the world's largest and fastest living birds.

Biomechanical studies of the fossil bones could show how speedy large terror birds were. But the behavior of these birds remains unknown, for example, whether the birds hunted in packs like velociraptors or individually like large predatory cats.

A 2005 study suggested that the giant birds may have used kicks to break the bones of their prey and extract marrow. Chiappe says he's particularly keen on running CT scans on the brain case of the new specimen and smaller phorusrhacids to learn more about the species.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //