Investigators at the Skidaway Institute of Oceanography (SIO), led by expert Aron Stubbins, say that they have discovered a way of analyzing data contained within Earth's glaciers, so that new knowledge could be gained on how the Industrial Revolution damaged far-away ecosystems and habitats.

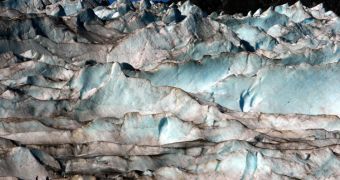

Thus far, studying such aspects has proven especially difficult. Determining how events that occurred centuries ago influenced ecosystems in places such as Antarctica is not a trivial task, but scientists say they can use glacial ice to study these phenomena with existing technologies.

The key to such studies, investigators say, is dissolved organic matter (DOM). The stuff can be found in glacial ice, and it contains a lot of carbon. By carrying out isotopic analyses of this carbon, researchers can explain how it behaved in Earth's atmosphere as the years passed.

Details of the research effort were published in the March issue of the top journal Nature Geoscience. The work was sponsored by a grant from the US National Science Foundation (NSF). The reason why glaciers were selected as targets is because they fuel much of the water downstream with carbon.

The SIO team hypothesizes that much of the DOM they are now finding in remote glaciers may have originated in ancient forests and peatlands that were covered in ice centuries ago. This contributed to preserving the matter relatively intact, which made researchers' jobs significantly easier.

At the same time, Stubbins believes that some of this carbon comes from the burning of fossil fuels and biomass, processes associated with the advent of the Industrial Revolution. The DOM may have been deposited by winds, snow, rain or other natural processes.

“In warmer ecosystems like in the temperate or tropical zones, once this atmospheric organic material makes landfall it is quickly consumed by plants, animals and microbial populations. But in cold glacier environments, these carbon 'signals' are preserved,” the team leader explains.

In the past, it was widely believed that glaciers in very remote areas of the planet were left untouched by the encroaching influence of higher atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations. This investigation demonstrates conclusively that the effects of pollution indeed spread worldwide.

“Because deposition of combustion products is a global phenomenon, all ecosystems may be receiving this 'subsidy.' Some aquatic systems previously thought to be pristine have, in fact, been affected by human activities for a century or more,” says Matt Kane.

The expert holds an appointment as a program director with the NSF Division of Environmental Biology. The DEB, the Division of Ocean Sciences and the Division of Earth Sciences co-sponsored the investigation.

“Glaciers will continue to provide a valuable and unique window into the role this deposition of organic material plays in a rapidly-changing environment,” Stubbins concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //