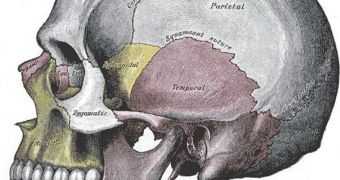

New finds in Africa seem to answer a few of the questions related to the evolution of the human race as we know it, and particularly about the way our skulls came to have the shape they have now, rather than look like that of early primates. Scientists at the George Washington University in the US have come across fossils belonging to Australopithecus africanus, a humanoid that lived on the continent more than 2 million years ago. They say that the adaptations showed by his face are most likely due to the need of ingesting large seeds and cracking open large nuts.

This again emphasizes the role of the diet in the lives of our ancestors, as a major part of our body developed in order to allow them to eat food considered to be of “last resort,” in case their favorite products were not available at a particular time of the year. Basically, the conformations our face bones have right now are an evolution from the rigid skulls those before us had, which they actually needed in order to consume wild fruit that were usually encased in hard shells.

“This research shows that our early ancestors were up to the task of eating some very challenging foods, and the approach of integrating anthropology and engineering promises to yield many more exciting results,” GWU researcher Brian Richmond, who is a paleoanthropologist and an associate professor of anthropology at the University, says.

“Because Australopithecus lived during a period in which climates were changing and unstable, the ability to eat foods that were difficult to process may have been an ecologically significant adaptation. Suppose that you’re an animal that eats soft fruits. When those fruits disappear, you only have a few choices: move to a different habitat, die, or eat something else. Nut cracking gave these early humans the ability to shift their diet when times got tough,” University at Albany associate professor and co-director of the human biology program David Strait, who is also the lead author of the new paper, adds.

“We would dearly love to be able to go back in time several million years ago and see what these fascinating creatures were eating, but we can’t. So these simulations are the next best thing. Fifty years ago, Louis Leakey called the first cousins of these creatures ‘Nutcracker Man,’ and maybe he was right after all,” GW University Professor of Human Origins Bernard Wood concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //