It would be nice to see all the mosquitoes and nasty insects dead with the first cold wave, and maybe see them no more the next spring.

But it doesn't work like that: even if we do not see them during the winter, they posses a number of specialized proteins, "heat-shock proteins", that enable them to pass through the chilly months.

A research made on flesh flies and other insects reveals that theirs protective heat-shock proteins are turned on immediately as the temperatures drop.

Before this research, just two such proteins were known in flesh flies. "Insects need heat-shock proteins in order to survive. Without these proteins, insects can't bear the cold and will ultimately die", said lead author David Denlinger, a professor of entomology at Ohio State University.

The team discovered 11 new heat-shock proteins that are turned on during diapause, an arrested development state that insects enter when temperatures decrease, and which can last for several months. "We certainly didn't expect to find that many proteins active during diapause," Denlinger said.

From insects to mammals, including humans, animals produce heat-shock proteins faced to extremely high temperatures. The proteins got their name as they were initially encountered in fruit flies exposed to high heat. In humans, these proteins are synthesized when we run a high fever. "But insects make these very same stress proteins during times of low temperature as well as during exposure to high levels of toxic chemicals, dehydration and even desiccation," explained Denlinger.

The team determined the number of genes turned on only during the flesh fly's dormant state, by comparing RNA from both dormant and non-dormant fly pupae (the developmental immobile stage between larva and adulthood), detecting the new 11 genes encoding heat-shock proteins.

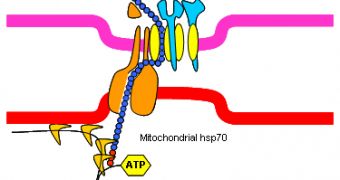

The team also examined one of the previously known two heat-shock proteins, Hsp70, in five additional insect species not related to the flesh fly, all common agricultural pest: the gypsy moth, the European corn borer, the walnut husk maggot, the apple maggot and the tobacco hornworm.

Hsp70 was turned on in all of them while in diapause.

When the Hsp70 gene was eliminated, the insects died at a low temperature (-15?C, or 5?F.) "This underscores the essential role of this gene for winter survival, suggesting that this particular heat-shock protein is a major contributor to cold tolerance in insects. It's highly likely that the other heat-shock proteins we found during diapause in the flesh fly are also important to an insect's ability to endure months of cold temperatures." said Denlinger.

"There may be steps we can take to disrupt the diapause process and make an insect vulnerable to low temperatures," Denlinger said. "At this point, the findings broaden our palette of players that contribute to cold tolerance in insects. The next step is to figure out the unique functions of each heat-shock protein. We assume it's not simply redundancy in the system, but that each protein makes a unique contribution somehow." he added.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //