Does violent video game playing make you less emotionally reactive to real-life violence? Ever since the 1980s, there's been an ongoing controversy surrounding such questions. Past studies have had surprising and disturbing results, showing for example that the effect of violent television exposure at an early age (between 6 and 11 years old) on later violent behavior is larger than the effects of low IQ, abusive parents, exposure to antisocial peers, and being from a broken home. Thus, it isn't surprising that people worry about video games. More than 85 percent of video games contain some violence, and approximately half of video games include serious violent actions. And, as it surfaced in 1999, the US Army uses video games in their attempt to desensitize the soldiers.

Although there is a real concern regarding this issue, most scientific studies haven't managed to make the leap from the virtual world out into the real one. "The main public concern with desensitization to violence is not that viewing media violence lowers physiological responsiveness to other media violence, but that it lowers responsiveness to real world violence," write Nicholas Carnagey, an Iowa State psychology instructor and research assistant, and Craig Anderson, an ISU Distinguished Professor of Psychology together with Brad Bushman, a former Iowa State psychology professor now at the University of Michigan and Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam.

The authors note that the expression "desensitization to violence" has been used in a rather vague manner which has confused both the public and the scientists. They define it more precisely as "a reduction in emotion-related physiological reactivity to real violence."

Their paper, which can be accessed here, documents that exposure to violent video games increases aggressive thoughts, angry feelings, physiological arousal and aggressive behaviors, and decreases helpful behaviors.

In order to test the "real life" effect of violent video games exposure the authors haven't used actual real life violence but short video clips of real life violence. After the participants played the games they were shown "a 10-min videotape of real violence in four contexts: courtroom outbursts, police confrontations, shootings, and prison fights. These were actual violent episodes (not Hollywood reproductions) selected from TV programs and commercially released films. In one scene, for example, two prisoners repeatedly stab another prisoner."

The experiments

They tested 257 college students (124 men and 133 women) individually. After taking baseline physiological measurements on heart rate and galvanic skin response -- and asking questions to control for their preference for violent video games and general aggression -- participants then played one of eight randomly assigned violent or non-violent video games for 20 minutes. The four violent video games were Carmageddon, Duke Nukem, Mortal Kombat or Future Cop; the non-violent games were Glider Pro, 3D Pinball, 3D Munch Man and Tetra Madness.

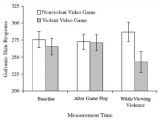

After playing a video game, a second set of five-minute heart rate and skin response measurements were taken. Participants were then asked to watch the 10-minute videotape of actual violent episodes. Heart rate and skin response were monitored throughout the viewing.

Although participants in the violent versus non-violent games conditions did not differ in heart rate or skin response at the beginning of the study, or immediately after playing their assigned game, their physiological reactions to the scenes of real violence did differ significantly. When viewing real violence, participants who had played a violent video game experienced skin response measurements significantly lower than those who had played a non-violent video game. The participants in the violent video game group also had lower heart rates while viewing the real-life violence compared to the nonviolent video game group.

"The results demonstrate that playing violent video games, even for just 20 minutes, can cause people to become less physiologically aroused by real violence," said Carnagey. "Participants randomly assigned to play a violent video game had relatively lower heart rates and galvanic skin responses while watching footage of people being beaten, stabbed and shot than did those randomly assigned to play nonviolent video games.

"It appears that individuals who play violent video games habituate or 'get used to' all the violence and eventually become physiologically numb to it."

The researchers also controlled for trait aggression and preference for violent video games. "One issue that arises frequently in the media violence literature concerns individual differences in susceptibility to media violence effects," the authors write. "If there are large individual differences in susceptibility to short-term desensitization effects, they would be revealed in the present study as significant interactions between the individual difference variables (violent video game preference; trait aggressiveness; gender) and the experimental manipulation of game violence. We found no such interactions, suggesting that the results are quite robust across individuals."

Thus, the authors conclude that the existing video game rating system, the content of much entertainment media, and the marketing of those media combine to produce "a powerful desensitization intervention on a global level." Carnagey warns that "several features of violent video games suggest that they may have even more pronounced effects on users than violent TV programs and films."

The mechanism

But how do video games achieve this "performance" of desensitizing the gamer to real life violence? What is the actual psychological mechanism at work?

The authors describe what they call the "desensitization procedures". Normally, the exposure to violence generates certain psychological reactions, such as fear or anxiety, but these procedures actively train the individual against having such reactions. These are normal reflex reactions and the desensitization procedures act like a sort of dressage. As you can see in the above graphs, the dressage really works - normally, exposure to violence increases heart rate and the galvanic skin response but in case of the people exposed to violent games they actually decreased (the participant was "immunized" against the emotional effects that usually accompany the perception of violence). Interestingly, the non-violent games increased the heart rate sensitivity to real life violence.

The desensitization procedures are constructed on the following principle: The individual is exposed to initially fearful stimuli but in a positive emotional context, such as a humorous context. This is often achieved by using cartoonish characters and by rewarding the violent actions. Moreover, the procedures are gradual, involving increasingly intense violent stimuli (the levels within a game).

The outcomes of these procedures are decreased perception of injury severity, decreased attention to violent events, decreased sympathy for violence victims, increased belief that violence is normative, and decreased negative attitudes towards violence. This in turn leads to a decreased helping behavior (lower likelihood of intervening or delays intervention) and to an increased aggressive behavior (a higher likelihood of initiating aggression, more severe level of aggression, more persistence in aggressing).

Authors note that this General Aggression Model has had various uses. "Whether induced intentionally (e.g., therapeutic systematic desensitization) or unintentionally, desensitization can be adaptive, allowing individuals to ignore irrelevant stimuli and attend to relevant stimuli. For example, desensitization to distressing sights, sounds, and smells of surgery is necessary for medical students to become effective surgeons. Desensitization to battle field horrors is necessary for troops to be effective in combat. However, desensitization of children and other civilians to violent stimuli may be detrimental for both the individual and society."

"It (marketing of video game media) initially is packaged in ways that are not too threatening, with cute cartoon-like characters, a total absence of blood and gore, and other features that make the overall experience a pleasant one," said Anderson. "That arouses positive emotional reactions that are incongruent with normal negative reactions to violence. Older children consume increasingly threatening and realistic violence, but the increases are gradual and always in a way that is fun."

"In short, the modern entertainment media landscape could accurately be described as an effective systematic violence desensitization tool," he said. "Whether modern societies want this to continue is largely a public policy question, not an exclusively scientific one."

The researchers hope to conduct future research investigating how differences between types of entertainment -- violent video games, violent TV programs and films -- influence desensitization to real violence. They also hope to investigate who is most likely to become desensitized as a result of exposure to violent video games.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //