The restrictions that the US federal government placed on embryonic stem cell research are having widespread negative consequences, not only for the country's role in the international scientific community, but also for research carried out using other types of stem cells.

These conclusions belong to an University of Michigan researcher, who carried out a meta-analysis of more than 2,000 scientific papers published on various lines of stem cells, and associated research.

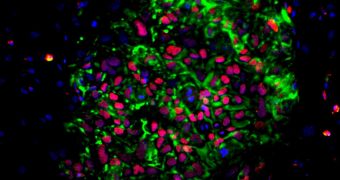

When the government stopped embryonic stem cell (ESC) research, authorities said that researchers could turn to using induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) for their studies. These cells were first discovered in 2007, and many believed that could eliminate the need for ESC.

IPSC can be produced from adult, fully-developed cells, which are coerced into reverting back to a pluripotent state. Once this is achieved, they can be guided through various methods to differentiate into other types of cells.

Many though that ESC were no longer needed once iPSC appeared. Yet, U-M sociologist Jason Owen-Smith and his team discovered that the two stem cell lines are not redundant or mutually-exclusive, but rather complementary.

As such, preventing the use of embryos for research is also hampering with experts' ability to use iPSC to produce viable new treatments for a host of dangerous conditions. The government basically damaged two stem cell lines in one fell swoop.

The United States have already fallen behind on the international scene, for the dominant position the country once held. Japan and Europe are now way ahead, since embryonic stem cell research can be conducted in many countries of the European Union.

“The incentives to use both types of cell in comparative studies are high because the science behind iPS cells is still in its infancy. As a result, induced pluripotent stem cells do not offer an easy solution to the difficult ethical questions surrounding embryonic stem cell research,” Owen-Smith explains.

Details of the new work will appear in the June 9 online issue of the esteemed journal Cell. Stopping ESC research “would derail work with a nascent and exciting technology,” the paper explains.

Scientists from the Stanford University and the Mayo Clinic were also a part of the research.

“We now have new data pointing to 'collateral damage' that could be caused by ill-conceived and politically motivated policy prescriptions. According to the data presented here, an entirely new technology, forged out of the crucible of political controversy, is at risk,” the study concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //