One of the things that always separates an addict from a normal person is the fact that they will repeatedly choose the behavior or substance that's got them hooked up despite being fully aware of the risks involved in doing this. A new study recently revealed the brain areas responsible for this behavior.

Some of the behaviors this study covers includes drugs, alcohol and cigarette use, overeating, gambling and kleptomania, to name just a few. Each of them carries its own set of risks, and yet addicts choose to engage in them regardless.

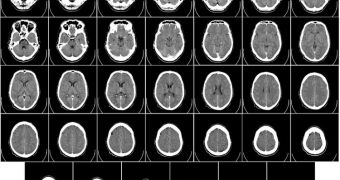

In the new investigation, University of California in Berkeley (UCB) neuroscientists were able to pinpoint the brain areas in which addicts perform cost/benefit analyses. In other words, these regions provide the calculations needed to explain their addictive/compulsive behavior.

Somehow, the type of neural activation patterns seen in these areas of the brain can easily make a person believe that it's OK to use drugs, or engage in other dangerous behaviors. The team found that the orbitofrontal and anterior cingulate cortex (OFC and ACC) control our decision-making processes.

Thanks to the new discoveries, researchers are now more optimistic that a series of novel therapies will be developed against conditions ranging from substance abuse to obsessive-compulsive disorders.

Details of the research effort were published in the October 30 online issue of the top journal Nature Neuroscience. The paper's principal investigator was UCB associate professor of psychology and neuroscience, Jonathan Wallis.

“The better we understand our decision-making brain circuitry, the better we can target treatment, whether it’s pharmaceutical, behavioral or deep brain stimulation,” the research scientist explains.

The questions that guided the research, he adds, were “What has the drug done to their brains that makes it so difficult for them not to make that choice? What is preventing them from making the healthier choice?”

His inspiration for conducting the work came after observing just the extent to which addicts would go in order to get a fix of the substance or habit that they were addicted too. When their urges kicked in, their better judgments were entirely clouded.

Their minds also became capable of justifying any sort of action to them. Self-deception is one of the most common behaviors that addicts display, and they are capable of carrying it out flawlessly.

“They get divorced, quit their jobs, lose their friends and lose all their money. All the decisions they make are bad ones. This is the first study to pin down the calculations made by these two specific parts of the brain that underlie healthy decision-making,” Wallis explains.

“We know beyond doubt that addiction is a complex brain disease with significant behavioral characteristics. This research is an important contribution to understanding how the disease works,” Susan E. Foster explains.

“The challenge going forward is to sharpen our understanding, translate this knowledge into effective medical treatments and new prevention strategies and ultimately find a cure for this disease,” she adds.

Foster holds an appointment as the vice president and director of policy research and analysis at the Columbia University's National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse (NCASA).

Funds for this research were provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), a part of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH).

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //