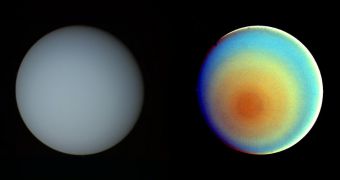

A quarter of a century ago, a NASA spacecraft flew past one of the most mysterious bodies in the solar system, the gas giant Uranus. The Voyager 2 spacecraft, on its way to exit the heliosphere, took the only close-up images of this planet and its moons.

The mission, which is still ongoing, is managed by experts at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), in Pasadena, California. It was there that project scientist Ed Stone and his team received the first transmissions of how the distant system looks like.

Chief among the discoveries the Voyager 2 space probe made was the magnetic north and south poles of the planet had little to do with the geographic ones, as they were located close to the Equator.

The main implication of this is that whatever materials flow underneath the surface of the planet do so at a much shallower depth than on Earth, Jupiter or Saturn. These movements are generating the peculiar magnetic field, JPL scientists found.

The flyby also revealed that Miranda, one of the smallest moons around Uranus, was not an ice-covered, crater-ridden world as initially thought. Experts were expecting to find an icy desert covered with poke marks, but that was not at all what the object looked like.

Voyager 2 revealed the existence of grooved terrain on the moon's surface, that was criss-crossed by linear valleys and ridges. These landscape features often came together to form chevron-like shapes.

The only conclusion that experts could draw from these observations was that Miranda had been exposed to bouts of tectonic and thermal activity in its distant past. This was a pleasant surprise for the research team, who was not expecting to find anything of interest.

“Voyager 2's visit to Uranus expanded our knowledge of the unexpected diversity of bodies that share the solar system with Earth,” Stone explains. He is now based at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), in Pasadena.

“Even though similar in many ways, the worlds we encounter can still surprise us,” he goes on to say.

After launching on August 20, 1977, the Voyager 2 space probe completed Jupiter and Saturn flybys, which were its primary objectives. It was then placed on a path that took it towards Uranus. It flew by the planet on January 24, 1986.

At closest approach, the spacecraft was some 81,500 kilometers (50,600 miles) above the gas giant's clouds. Uranus is located 3 billion kilometers (2 billion miles) away from the Sun.

After the flyby, the probe headed towards Neptune, which it reached in August 1989. Currently, it is heading towards interstellar space, away from the protective heliosphere that the Sun creates around planets in our solar system.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //