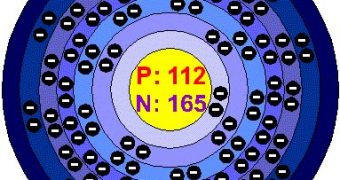

Ununbium (Uub) is the 112th element of the periodic table, often alternatively called eka-mercury and a systematic temporary element, part of the superheavy elements called transactinides.

Usually, researchers have a hard time catching the slightest glimpse of the superheavy elements at the far edge of the periodic table, because of their extremely short lifespan.

Now, a team of researchers led by Robert Eichler of the Paul Scherrer Institute in Villigen, Switzerland, in collaboration with the University of Bern, also in Switzerland, has gone a step further and analyzed the chemistry of the 112th element, ununbium, which seems to bond with other elements in the same way as its ordinary relatives, zinc and mercury.

In fact, by fusing a zinc atom with a lead atom by accelerating zinc nuclei into a lead target in a heavy ion accelerator, was in fact the first method of creating unubium, on February 9, 1996 at the Gesellschaft f?r Schwerionenforschung (GSI - Heavy Ions Research Society) in Darmstadt, Germany.

"In principle, we are proving whether the good old basic systematics of chemistry - the periodic table - is a valid ordering principle also for transactinides," said Eichler.

They bombarded a piece of plutonium 242 (Pu) with an intense beam of calcium 48 ions inside a vacuum chamber, and, as earlier applications indicated, the two fused from time to time into an isotope of element 114 (with 114 protons and 287 neutrons), which would rapidly decay into "ununbium," or element 112 (112 protons and 283 neutrons).

But in the new technique, the bombardment ejected its products into the chamber, where a stream of helium gas ushered them to a chilled gold-coated detector that was warmer on one side than the other. The next step was to introduce the inert gas radon and the element mercury, which would lie in the same column as element 112 on the periodic table, so that the atoms of each element would stick to the detector at the point where its temperature was just low enough to let them form chemical bonds with gold.

There were previous speculations that ununbium's relatively charged nucleus might contract its electron cloud, thus making the atom largely unreactive, like the rare gas radon (Ra).

After that, the scientists searched for signs of ununbium decay and compared their detector positions with those of the two other elements. They observed a grand total of two ununbium decays on the warmer, mercury-grabbing end of the detector. These also indicated a significantly long half-life for these superheavy elements, of a few seconds, as they predicted.

Although ununbium is not yet recognized as an official element, the researchers said they have achieved their goal of confirming reports that the bombardment process produced element 112 and that getting a bead on its chemistry was a bonus.

"We succeeded in both and this makes me as a chemist very happy," Eichler says. "There have been so many varying predictions about the chemical behavior [of] element 112. We wanted finally to know."

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //