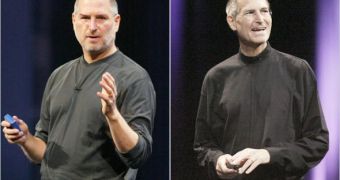

Prior to taking his last two medical leaves from Apple, Steve Jobs fought off a rare form of pancreatic cancer that ended with a liver transplant and some medication. Or has the ordeal ended?

Certainly not, those who are well accustomed with the disease say, according to CBSNEWS. And so it would seem, given that Jobs resigned from his CEO position with Apple this week.

The media agency has compiled a number of doctor reports and interviews to draw a potential picture of Steve Jobs’ medical condition at the moment. From the looks of it, Jobs is not out of the woods yet. Not by far, actually.

According to the report, Dr. Richard Goldberg, a neuroendocrine tumor expert at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, told USA Today that "People can co-exist with this disease for years."

Dr. Goldberg did not come into contact with Apple’s former CEO, but did say that things can get bad when the liver begins to fail.

"People can go downhill pretty quickly," Goldberg said. "When you hit the wall, you hit the wall."

According to Dr. Margaret Tempero, a pancreatic cancer expert at the University of California-San Francisco, more common types of pancreatic cancer generally won’t allow patients to live more than a year.

However, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor are generally more curable. And that’s what Steve Jobs had in 2009 while on a medical leave.

Dr. Tempero said liver transplants for neuroendocrine tumors are "occasionally successful, but it's a real long shot.”

It is known that up to 80 percent of patients who treat this type of cancer by getting a new liver will have at least five years to live.

But even the liver transplant itself can do damage. According to Dr. Simon Lo, director of pancreatic and biliary diseases at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, a liver transplant also has the potential to further the cancer's spread.

Dr. Lo said that this is the most likely serious complication from a liver transplant.

The main cause are actually the immunosuppressant drugs, which transplant patients are generally given.

If the cancer would somehow return, the drugs would have the ability to hinder the body's natural defense mechanism, allowing the disease to grow faster than normal.

"Whenever you put patients on immunosuppressant medications, there's always a risk that it could take away natural resistance, so the cancer could grow faster," Dr. L said.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //