A team of doctors has determined that it is possible to reduce the intensity of chronic chest pains in patients by injecting stem cells into their hearts. The cells themselves are extracted from the recipients' own bone marrows, and they apparently work by promoting blood vessel growth.

This approach is especially well-suited for hard-to-treat chest pains, which do not respond very well to standard medication. Patients suffering from this condition reported feeling better, and also being able to exercise for longer, after receiving the injections.

Details of the new approach appear in the latest issue of the medical journal Circulation Research. The lead investigators for the new study was Northwestern University researcher Douglas Losordo.

Procedures that are currently used to address chronic chest pains, such as for example stents and angioplasty, usually do not reach small blood vessels inside the heart. These vessels are usually damaged in patients who complain of such pains.

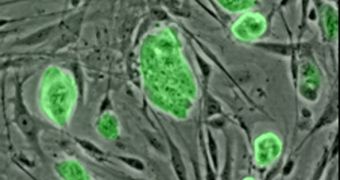

What the injected stem cells do is they contribute to the growth and development of these small blood vessels, improving circulation and preventing ischemia (the lack of blood circulation in a certain area).

Losordo takes an innovative appraoch to addressing these types of pains, in the sense that he is among the very few researchers using the blood vessel growth-promoting stem cell type CD34+, Technology Review reports. He has been involved in this line of research for more than 10 years.

Official statistics provided by the American Heart Association (AHA) indicate that more than 850,000 US citizens suffer from lingering bouts of chest pain every single year. The condition, known as refractory angina, cannot be addressed with medication, angioplasty, or stenting.

“These cells seem to represent one of the natural mechanisms for helping to repair damaged tissue. We're taking a preprogrammed repair mechanism and simply trying to leverage that in patients who have been damaged over the course of many years or decades,” Losordo explains.

“I think that this is a promising study, because it was so carefully done and because this patient population can be very incapacitated,” comments Richard Lee. The expert holds an appointment as the head of the cardiovascular program at the Harvard Stem Cell Institute.

Lee is also a cardiologist at the Brigham and Women's Hospital, in Boston, Massachusetts. Losordo conducted his study on 167 participants, all of which suffered from at least 20 bouts of pain every single week.

People who got the injection reported considerably fewer bouts of pain after the procedure. They also said that the intensity of the pain they felt diminished as well. The same reports were not provided by members of the control group.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //