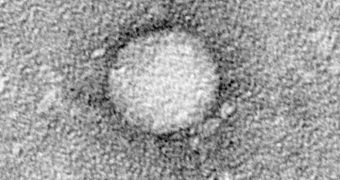

By using induced pluripotent stem cells as a starting point, researchers in the United States say they can obtain liver-like cells that could help them crack the mystery surrounding hepatitis C. The condition is puzzling because it produces different effects on patients

The overall effects are the same – mostly inflammations followed by organ failure – but the way in which these symptoms manifest themselves differ from patient to patient. Many experts believe that minute genetic differences may be to blame for this.

Additionally, past investigations have revealed that some people simply appear to be immune to the disorder, whereas others are very susceptible of developing it. By studying liver cells from all types of people, researchers believed that they could pinpoint the genetic variations.

But obtaining, and working with, the cells has proven to be very difficult, primarily because they tend to lose their function and form once they are removed from the liver. This is where the iPSC step in.

The new technique is proposed by a group of experts made up of specialists from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), the Rockefeller University and the Medical College of Wisconsin.

The main advantage of working with iPSC is that the stem cells can be collected from the developed body, thus avoiding the difficulty of getting them from viable embryos. Mature cells harvested from the body can then be reverted back to a pluripotent stage, and then made to develop into liver cells.

Researchers can then infect these cultures with hepatitis C, and observe the effects that the condition has on different types of cells. Exact details of how this is done are listed in the latest issue of the esteemed journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

“This is a very valuable paper because it has never been shown that viral infection is possible” in cells derived from iPSC, comments Baylor College of Medicine assistant professor of molecular and cellular biology Karl-Dimiter Bissig, who was not a part of the investigation.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //