Intestinal stem cells can now be grown in unlimited quantities, thanks to a new technique developed by researchers with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), in Cambridge, and Brigham Women's Hospital (BWH).

The group says that the stem cells obtained in this manner can then be used to create high-purity mature intestinal cells of different types, with great potential therapeutic value for numerous conditions.

One of the most interesting uses for cells obtained in this manner is as a medium for testing new drugs, a process that would otherwise require human clinical trials. By having unrestricted access to human cell samples, researchers will from now on be able to conduct multiple studies faster than ever.

Diseases such as ulcerative colitis could become easier to treat thanks to treatments developed in this manner, the team explains. The mature intestinal cells that can be derived from this stem cell population are used to fulfill a variety of roles in the small intestine.

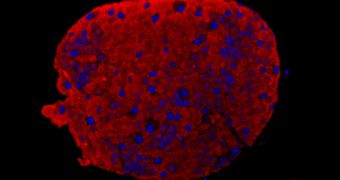

The reason why these cells could not be grown in bulk until now is that their immature state, which is essential for their ability to develop into multiple types of adult cells, only endures when they are in contact with specialized cells called Paneth cells.

What the MIT/BWH team did was basically find a way to replace these Paneth cells. This allowed them to start manipulating the stem cells in a way that was not possible before. The replacements are two small molecules, the team writes in the December 1 online issue of the journal Nature Methods.

“This opens the door to doing all kinds of things, ranging from someday engineering a new gut for patients with intestinal diseases to doing drug screening for safety and efficacy. It’s really the first time this has been done,” says one of the senior authors on the study, Robert Langer.

The expert holds an appointment as the David H. Koch Institute Professor at MIT, and as a member of the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research.

“If we had ways of performing high-throughput screens on large numbers of these very specific cell types, we could potentially identify new targets and develop completely new drugs for diseases ranging from inflammatory bowel disease to diabetes,” concludes Harvard Medical School /BWH associate professor of medicine, Jeffrey Harp.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //