In a new investigation, researchers demonstrate a potential that tissues obtained from a patient's own stem cells have of turning cancerous under certain conditions. The work is meant as an alarm signal for researchers working with stem cells, who are advised to pay special attention to this possibility.

The investigation does not mean that applying stem cell research practically will lead to a grow in cancer rates. It is merely a warning that this is a possibility. If the work is confirmed by other studies, then researchers in the field will have to adjust their work accordingly.

Scientists from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem say that great emphasis is placed today in the scientific community on developing stem cell technology to a point where a patient's damaged tissues could be replaced with healthy tissues, grown from their own stem cells.

Gaining this ability would have major implications for how medicine is carried out. The need for transplants would be eradicated. A person could get a new heart made from their own stem cells, so there would be no possibility of the body rejecting the transplant.

What the team is saying is that researchers should be cautious when developing new treatments, to ensure that they are not unwillingly substituting one disease with another, AlphaGalileo reports.

Stem cell research has come a long way since it developed as a science. Several years ago, Japanese scientists managed to create embryonic-like stem cells by “reprogramming” adult stem cells. These new cell populations are called induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC).

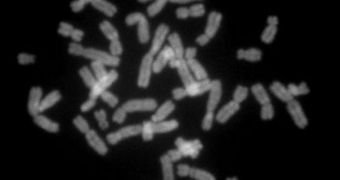

One of the things that the HUJ team noticed was that, when growing stem cells in cultures for prolonged periods of time, the populations tended to exhibit mutations in their chromosomes.

The same type of changes can also be observed in cancerous tumor growth, the group explains. The modifications affect iPSC too, says expert Nissm Benvenisty, the leader of the research group.

The researcher holds an appointment as the Herbert Cohn Professor of Cancer Research at the HUJ Silberman Institute of Life Sciences. The work was conducted with post-doctoral fellow Yoav Mayshar and PhD student Uri Ben-David.

“Our findings show that human iPS cells are not stable in culture, as was previously thought, and require reassessment of the chromosomal structure of these cells,” Benvenisty explains.

“Also, our work shows for the first time the gene expression changes that accompany these chromosomal aberrations found in the culture, paving the way for our beginning to understand the mechanism by which these changes occur,” he adds.

“The chromosomal changes in these iPS cells require everyone to exercise great care in continuing to work with them, since these changes apparently will influence the differentiation potential and the tumorigenic risk of these cells,” the expert goes on to say.

He also says that the use of the research method the team developed to arrive at these conclusions can be extended to analysis of other cell types too, such as for example cancer cells. “It is relatively simple to use and enables one to observe the changes without having to directly analyze the DNA of the cells,” Benvenisty concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //