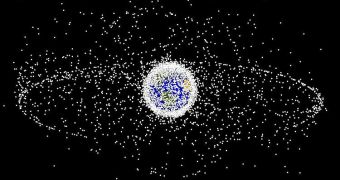

It has become rather apparent in recent times that Earth's orbit is literally suffocated in junk. Debris from satellite launches, spent rocket stages and satellites themselves are floating freely in microgravity, speeding around the planet at mind-boggling speeds. They can in turn impact other satellites, causing a cascade of debris that can cause a chain reaction. They also threaten the life of astronauts on the International Space Station (ISS), as an impact would have devastating consequences. But removing the junk from orbit is difficult, perhaps even more so than researches first thought.

The conclusion belongs to a new scientific study, which looked at the challenges associated with cleaning up our planet's orbits. The research paints a bleak picture of the future, showing that removing the tiny pieces of junk from space is actually a lot more difficult than anyone imagined. This is mostly due to the fact that debris tends to remain in orbit for longer time frames than initially calculated. The new research was conducted by experts in the United Kingdom, at the University of Southampton.

The group learned that global warming and climate change are having an unexpected effect on Earth's thermosphere. The atmospheric layer is apparently contracting, which means that the composition and function of the upper atmosphere is gradually changing. The main reason why this happens is the fact that increasingly large amounts of the dangerous greenhouse gas carbon dioxide are accumulating in the atmosphere, the British team says. As a side-effects, satellites and space debris are kept floating in microgravity for extended periods of time, before they orbits degrade, and they reenter the atmosphere.

Under these circumstances, it stands to reason that, even with advanced orbital clean-up programs (which by the way are virtually inexistent), the job experts would have just got a lot more difficult. It would be a lot easier to remove space debris if the Earth's atmosphere contributed to the effort as well, analysts say. “The fact that these objects are staying in orbit longer counteracts the positive effects that we would otherwise see with active debris removal,” says University of Southampton School of Engineering Sciences expert Hugh Lewis.

“Our study shows that if we double the number of debris objects we can remove each year, we can get back on track with reducing the debris population. Achieving this target, however, will be challenging,” Lewis explains. “An operational consequence of this important new finding is that LEO satellites, including debris, may remain in orbit longer than expected,” concludes Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) Space Sciences Division specialist John Emmert, quoted by Space.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //