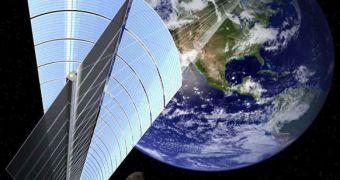

In the past couple of years, the idea that we could soon become able to generate a lot of electrical current through solar power plants in space has made many tremble with anticipation. A number of partnerships between private companies and space agencies like NASA and the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) already exist, each more ambitious than the other. But some voices now argue that the enthusiasm may have been somewhat misplaced, and that the technical challenges are too great to be overcome in the next five to ten years, Space reports.

This is not to say that it's impossible to construct such an instrument outside of the Earth' atmosphere. There is nothing in our current technologies that could prevent us from doing so. But from paper to launch pad there's a long way to go, and a number of experts point to the International Space Station (ISS), as an example of the blood, sweat and tears associated with constructing an orbital structure. The main critic is that the new agreements make promises they can't keep, in the time the partners decided for themselves.

Just last week, the American company Solaren Corp. wanted to close a 15-year contract with utility giant Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E). The agreement says that the former needs to supply the latter with electricity from space-based solar power plants come 2016. The plan was even proposed by California regulators in their meeting. The goal is pretty far-fetched, seeing how current logistics do not allow for the deployment of such complex structures at this point. There are also no ships like the space shuttle, on which spacewalkers could base their extra-vehicular activities (EVA), as they assemble the power plant.

If the plan is to use components that automatically interlock, then such technology should have started being researched many years ago. All past experiences with space agencies show that such an endeavor cannot be completed in five or six years, but nothing is impossible. JAXA, for example, set a much more attainable goal for itself, saying that its first such power plant was scheduled to take to the skies in the 2030s. “The problem is that we're treating space solar power as something that has to compete with coal right now. Nothing can compete with coal,” New York University physicist Marty Hoffert says.

The tricky business with harvesting power directly from space is the fact that you cannot exactly anchor the power plant to Earth. It therefore needs a method of transmitting the generated electricity back to Earth. Experts propose that this can be achieved through either lasers (highest capacity, but prone to interferences from clouds), or microwaves, which carry less current, but can penetrate clouds. A permanent decision on which is best has yet to be taken. On the bright side, the space structures would escape the constraints of the day-night cycle and of moody weather back on Earth.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //