A team of investigators at the University of California in Los Angeles (UCLA) has recently determined that exposure to large amounts of social stress can make the brain respond by modifying the way the immune system responds to threats. These modifications can open the way for numerous diseases or infections to set in, which is why eliminating social stress should become a priority for most people.

This type of stress appears for example when you're getting ready to give a speech. The inability to connect with other people at a party can also be a triggering factor, as could the anxiety associated with giving a job interview. All these social stressors (stress factors) have a severe influence on the human brain, which responds by affecting the immune system. The work was conducted by lead study author George Slavich and senior author Shelly Taylor.

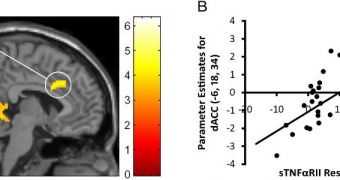

Slavich, a postdoctoral fellow at the UCLA Cousins Center for Psychoneuroimmunology, argues that people who tend to show greater neural sensitivity are also very likely to greater increases in inflammatory activity when subjected to social stress. The increase can be adaptive, explains Taylor, a UCLA professor of psychology, but that doesn't mean that the risk a person has of developing a chronic inflammation are any lower,. These conditions include asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, cardiovascular disease, certain types of cancer, and depression.

“It turns out, there are important differences in how people interpret and respond to social situations. For example, some people see giving a speech in front of an audience as a welcome challenge; others see it as threatening and distressing. In this study, we sought to examine the neural bases for these differences in response and to understand how these differences relate to biological processes that can affect human health and well-being,” Slavich says.

“This is further evidence of how closely our mind and body are connected. We have known for a long time that social stress can 'get under the skin' to increase risk for disease, but it's been unclear exactly how these effects occur. To our knowledge, this study is the first to identify the neurocognitive pathways that might be involved in inflammatory responses to acute social stress,” the expert adds. Details of the work have been published in the latest online issue of the esteemd journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //