As I was browsing through my old college notes yesterday, I stumbled upon some lectures that dealt with various theories on the redistribution of wealth in societies. This is not such a complex subject as it may first appear. Its main area of interest is proposing, and arguing for, various ways of using the money a society generates, and redistributing it to the less fortunate. This is done in all types of political systems, from capitalistic to communist, through a variety of means, including income taxes and the like. One of the authors that I remembered taking a liking to was John Bordley Rawls, a liberal, moral and political philosopher who influenced the way people look at how redistribution should work.

Rawls was born in the Unites States, on February 21, 1921, and died aged 81, on November 24, 2002. His greatest work, and the book that I had to study in college, is called “A Theory of Justice” and was published in 1971. I remember being fascinated by a host of new ideas that at the time I didn't know even existed. I think I can safely say that it's because of this book that I learned to look at the way societies are set up differently than I did before. One of the things I appreciated most about the work is that it doesn't seek to persuade you that existing systems of redistribution are necessarily flawed.

His work was heavily influenced by well-known and respected philosophers and thinkers, including among others Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Immanuel Kant, John Locke, and Thomas Hobbes. As a direct result, Rawls took to using the concept of a social contract as a means of demonstrating the idea that would later become so widely-known, that of “Justice as Fairness.” The liberty principle and the difference principle became the foundation of his new theory, and the book, published again and again, has become a must-read for all students pursuing philosophy, political sciences and related fields.

The idea of a social contract refers intuitively to the way people go about organizing themselves into states and nations. The ultimate goal in these forms of organizations is naturally maintaining social order. An example of this, taken to extremes, is represented by authoritarian regimes, which go out of their way to preserve the social contract that allowed them to come to power. But while their actions may be founded in solid philosophical principles, they tend to neglect the fact that the social contract needs to be agreed upon by both parties, the rulers and the ruled. When this balance is broken, anarchy and authoritarianism are the only possible outcomes.

One of the basic principles for social contracts is the fact that individuals willingly pass on some of their sovereignity to the state, reducing their own freedoms for the greater good. Most people in a society, for example, renounce being able to kill others, steal, or otherwise behave unethically simply because their own decisions to endow the state with more capacities has led to the creation of a police force – or other group that maintains order – which is authorized to use whatever means necessary to weed out such behavior from that particular society.

Returning to how Rawls used this idea, I found it amazing how he gave it an unexpected twist. Rather than referring to it like his predecessors did, the philosopher constructed a new view, called the “original position,” which is a highly advanced form of the social contract. The main point of view in “A Theory of Justice” is that liberty and equality, as concepts, need to be balanced and reconciled within a society based on mutually-accepted principles. He also introduced the notion of “veil of ignorance,” which is basically stating that, when notions of justice are developed, individuals participating in this effort should be blind to facts about themselves that may hinder their decisions.

This is naturally hard to do, but Rawls believes that it's only through cooperation that societies can be founded on long-lasting principles. In the past, many thinkers identified the main issues facing redistribution, and organizing societies in general, were related to when one's individual freedoms stopped, and another person's began. Everyone has to be free, philosophers have been saying for centuries, but accomplishing this freedom is harder than it appears. This is most often than not due to human nature, as individuals tend to be selfish in this type of issues.

People like to achieve the maximum amount of liberty of action for themselves, but oftentimes remain oblivious that their actions may be infringing on others' freedom. The role of the state, and of the social contract, is to balance these two out, and all forms of political systems do so in one way or the other. What varies between political approaches is their individual views and acceptance of the social contract, and the type of redistribution scheme that they adopt. Those of conservative and libertarian beliefs will, for example, argue against the progressive income tax as a means of redistribution.

In setting up the boundaries of his theory, John Rawls also turns to game theory for assistance. This is my favorite field of mathematics, and one that I studied extensively in a class called “Rationality and decision in conflict analysis.” Basically, game theory refers to every situation possible as a “game,” in which “ players” (individuals, corporations, groups, states, and so on) adopt various strategies to maximize their own advantage. Things may seem fairly clear cut at first, but, as you progress in the notions that many authors set forth, you begin to realize that nothing is really as it seems.

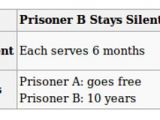

Let's take the simplest and most clear example of a game that was made famous decades ago, and is called the Prisoner's Dilemma. It goes like this: “Two suspects are arrested by the police. The police have insufficient evidence for a conviction, and, having separated both prisoners, visit each of them to offer the same deal. If one testifies (defects from the other) for the prosecution against the other and the other remains silent (cooperates with the other), the betrayer goes free and the silent accomplice receives the full 10-year sentence. If both remain silent, both prisoners are sentenced to only six months in jail for a minor charge. If each betrays the other, each receives a five-year sentence. Each prisoner must choose to betray the other or to remain silent. Each one is assured that the other would not know about the betrayal before the end of the investigation. How should the prisoners act?”

In this case, the best possible solution for both of the players is remaining silent. Both would receive 6 months in jail for a lesser charge, but they would both go free afterwards. The worst outcome for both would be if they both defect, and receive five years in prison. The reason why this is labeled as a cooperative game is because each of the players is tempted to defect. If the other one remains silent, then the person that told everything to the police goes free, while the other gets 10 years. But both players imagine that the other has been offered the same conditions, and are afraid of spending five years in jail. The logic underlining this scenario, and others, makes game theory an amazing field.

The way Rawls sees things is that societies should be built on a “maximum” strategy, which means that they should focus themselves on maximizing the potential benefits for the least well-off. As the man himself puts it, “The basic structure is just throughout when the advantages of the more fortunate promote the well-being of the least fortunate, that is, when a decrease in their advantages would make the least fortunate even worse off than they are. The basic structure is perfectly just when the prospects of the least fortunate are as great as they can be.”

Overall, the philosopher proposes two principles of justice. The first one reads: “First: each person is to have an equal right to the most extensive scheme of equal basic liberties compatible with a similar scheme of liberties for others.” The second one deals with how social and economic inequalities should be arranged, so that 1) they are to be of the greatest benefit to the least-advantaged members of society, and 2) offices and positions must be open to everyone under conditions of fair equality of opportunity. Rawls underlines, however, that large social and economic differences, even when benefiting the worst-off, tend to undermine the value of political liberties, and also the fair equality of opportunity.

But I'm getting into too many details. Suffice it to say that the book is a wonderful read if you are into learning more not about political systems, but about the reasoning behind setting them up in the manners they exist today. When you hear some saying that either democracy, socialism or communism doesn't work, they are not necessarily referring to the applied cases, such as the system in a particular country. They could be talking about how the schemes used to redistribute wealth, and the social contracts involved, may be unfair and unequal.

Naturally, many authors and respected thinkers criticized Rawls' work, or added to it. The author of “Understanding Rawls: A Critique and Reconstruction of A Theory of Justice,” University of Massachusetts Amherst professor Robert Paul Wolff took, for example, to arguing that Rawls' approach was supporting the capitalistic establishment and the status-quo. Written from a Marxist point of view, his work shows that Rawls' theory does not allow for existing practice in establishing what justice is to be modified. He also says that “A Theory of Justice” eliminates the possibility that injustice may already be embedded in capitalist social relations, private property, and the market economy.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //