Experts at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have demonstrated in a new mouse-model study that the animals that are prevented from remembering data collected during the day while sleeping tend to have “fuzzy” memories the next day, as opposed to mice who were left to sleep undisturbed. The research further goes to show that theories saying that the most important part of the process that transforms short-term memories in long-term ones during sleep are true, and this new study could easily prove to be a welcomed addition to the line of thought seeking to learn the purpose of sleeping.

The investigation was conducted by scientists at the MIT Picower Institute for Learning and Memory RIKEN-MIT Center for Neural Circuit Genetics, led by the Picower Professor of Biology and Neuroscience Susumu Tonegawa. The results appear in the June 25th issue of respected scientific journal Neuron.

“Our work demonstrates the molecular link between post-experience sleep and the establishment of long-term memory of that experience. Ours is the first study to demonstrate this link between memory replay and memory consolidation. The sleeping brain must replay experiences like video clips before they are transformed from short-term into long-term memories,” the expert argues.

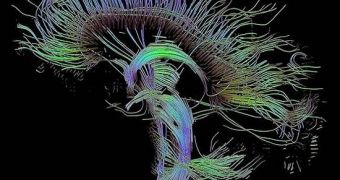

Over the years, a large number of studies has shown that the brain region known as the hippocampus plays an essential part in storing short-term memories for a while, before finally relaying them to the neocortex, which is widely believed to be the area where they are permanently stored. However, at this point, researchers investigating the human brain don't really have a clue as to what mechanisms and pathways are employed in this process, and how exactly memories are shaped into long-term ones.

In their investigation, the MIT researchers looked at a pathway in the hippocampus known as the trisynaptic pathway. This conduit passes through all three “parts” of the nerve center, and carrier electrical impulses in and out of it. “We demonstrated that this pathway is crucial for the transformation of a recent memory, formed within a day, to a remote memory that still exists at least six weeks later,” Tonegawa further explains, quoted by PhysOrg.

“Our conclusion is that the trisynaptic pathway-mediated replay of the hippocampal memory sequence during sleep plays a crucial role in the formation of a long-term memory. We have demonstrated that in the mutant mice in which the trisynaptic pathway is blocked, this replay process during the slow-wave sleep is impaired,” the researcher concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //