Which is the storehouse of our memories? A new research made at the University of Liege, in Belgium, and published in the "Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences", has made a connection between sleep, brain changes and memories' quality 6 months after an event has taken place. Memories appeared to be processed first in the hippocampus, then transferred for long term and consolidated into the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), turning them stable to other stimuli.

"This is the first time we could confirm in humans a number of predictions based on animal research. In particular, we could show that the hippocampus plays only a temporary role for storing new semantic information, and that other brain regions slowly take over its function", co-author Steffen Gais told PhysOrg.com.

Memory formation has two stages: molecular processes at synapses (connections between brain cells), and storing within various nuclei. Storing starts in the hippocampus, and in several months, memories are passed to the prefrontal cortex. The precise mechanism of this is not known, but the new research reveals that a good night's sleep following the learning of new information affects this.

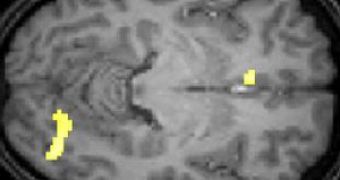

18 subjects had to learn 90 word pairs, and while recalling them (as much as they could), brain activity was assessed through fMRI. 50 % of them slept normally that night, and the others stayed awake all night. Two days later, all the subjects repeated the experiment. As expected, sleep-deprived subjects had forgotten many more word pairs, and fMRI images showed that brain activity in the right hippocampus was much higher in those who had slept.

"Our original hypothesis about the time-course of hippocampal involvement predicted an immediate decrease - not an increase - in hippocampal activity after sleep", said Gais.

Six months later, the subjects (who hadn't been told this) repeated the test. Of course, they had forgotten most word pairs, and those in the sleeping group recalled a few more word pairs than the others. But the surprise was revealed by the fMRI images, which revealed in this group increased brain activity, in the left ventral medial prefrontal cortex (but not in the hippocampus), compared to the sleep-deprived subjects, whose brains were more active in the hippocampus area.

This discovery shows that lack of sleep following learning impairs changes, as required for memory consolidation. But, the sleep-deprived individuals still recalled similar numbers of word pairs as the other subjects, as the hippocampus and neocortex store memories in a redundant manner, with one difference: the prefrontal cortex is more refractory to interfering stimuli.

"Our findings bring us a little closer to understanding how the brain stores and processes new memories and might prove helpful in improving memory, for example, in conditions like Alzheimer's", said Gais.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //