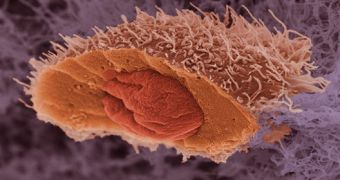

A newly-designed substance has been developed specifically to combat skin cancer carcinomas, the most common form this disease takes in patients. It approaches the illness from 2 directions. First of all, it is a virus that incites an increased immune system response, which then directs itself on the tumors. Secondly, it also attacks the tumors directly, by shutting down genes that the cancerous cells use to replicate inside the body.

Mouse lab tests have shown great promise for this new technique, which managed to halt the development of metastasis in animal models suffering from cancer. Ever since 2006, when Nobel Prize winners Craig Mellow and Andrew Fire discovered their huge potential, RNA (ribonucleic acid) molecules have been used to induce this effect, as they are now the "workhorse" of genetics. The tiny nucleic acids can be used as a means of transport in both biological and artificial therapies, including viruses and nano-technology.

"We used this method in order to drive the tumor cells to suicide. Every single body cell is equipped with a corresponding suicide program. It is activated, for example, if the cell becomes malignant. It dies before it can do any more harm. But, in tumors, a gene is active that suppresses this suicide program. We have pinpointed this gene and switched it off by using RNA interference," explained Experimental Dermatology Laboratory professor Thomas Tüting.

The scientists used an ingenious way of inciting the immune system to respond. They hid the RNA components into the substance, which prompted the body to elaborate a response and attack the intruders. This happened because some fragments of RNA are interpreted by the immune system as being part of a virus, as some viruses actually use nucleic acids to move around.

"The beauty of this method is that we can attack the cancer with one designer molecule along two completely different routes. This way the tumor is deprived of opportunities of sidestepping the attack that make successful therapy so difficult in other cases," explained Bonn University Institute of Clinical Chemistry and Pharmacology professor Gunther Hartmann.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //