Astronomers say it could be possible that at least a few of the earliest stars ever to appear in the Universe are still lit and alive, more than 13 billion years after they appeared. Some of them might even be inside our galaxy, the Milky Way.

The Cosmos as a whole I more than 13.75 billion years old, but the first stars and galaxies did not appear until several hundred million years later. As such, massive and old galaxies including our own by harbor stars that are around 13.4 billion years old.

These are the conclusions of a new computer simulation, which was conducted by German researchers at the University of Heidelberg. The group was led by expert Paul Clark. Details of their work were posted online in the journal arXiv on January 28.

In addition, the experts also published their investigation in the February 3 issue of the top journal Science. The prestigious magazine published the work because it challenges some of the most widespread ideas about how the early Universe looked like.

One of them holds that, 300 to 500 million years after the Big Bang, the earliest stars appeared, burned for a few million years, and then died out. The new data suggest they were not extinguished, but rather continued burning to this day, Science News reports.

The German research team proposes a new mechanism that would explain how stars capable of enduring for such a long time could have been produced in the early Universe. Thus far, experts believed that only massive stars could be generated in those conditions.

Working together with colleagues from the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics (MPIA), in Garching, Clark managed to develop a scenario in which smaller, less massive stars were formed in the same conditions. The MPIA team was coordinated by expert Thomas Greif.

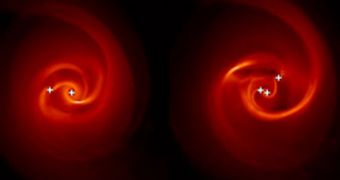

The new theory holds that some stellar nurseries in the early Universe did not create single, massive stars, but rather several stellar “embryos” at a time. As these small stars would have been very closely spaced to each other, they would have exerted strong gravitational pulls on each other.

The largest of them would have driven the smallest out of the group. The team hypothesizes that this usually happened before the runaway star got a chance to grow to massive sizes. The main implication for this is that the stellar object was not short-lived.

Some of these small stars may have survived to this day. The only condition is for them to have been expelled from their stellar nurseries before they grew to more than 80 percent the mass of the Sun.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //